“How did you get the job baking at Fred Segal?” my daughter asked me in the car yesterday. Fred Segal as in, the warren of boutiques in Santa Monica (now closed) and a smaller one in West Hollywood, the neighborhood in which I landed at 24, with $2000 and a standard shift Subaru and the idea that I was going to be a movie star.

I had no reason to believe the stardom would happen but for desire, and while the other wannabe starlets were taking dance lessons and voice lessons and making sure every last part of themselves gleamed, I was living in a house with a bunch of 22-year-old guys, one of whom was dealing pot, which meant a steady flow of other 22-year-olds guys in and out of the house all day and tinkering with conked-out motorcycles on the concrete pad out back. I did not smoke pot and was already feeling old as well as whatever the opposite of gleaming is, and spent most of my first month driving Sunset Boulevard to the beach because I had the idea this was what you did in LA, and also cooking and cleaning for the 22 year-olds, until the money ran out and I applied for the baking job at Fred Segal. The owner, a nice red-headed guy named Shane, said he’d give me a call. He didn’t, and so a week later I walked in with a poundcake and some cookies I’d made at home. Shane gave me the gig, which I held for about a year and a half, until my mom flew out for a visit and had me pose in front of the pastry case displaying the Fruit Box cake and brown sugar scones and date-nut bars and lemon bars I’d made, and I could feel nothing but shame.

I might say that the actors in “The Bear” are not much older than I was then, but I’m not sure age is a point of connection here or in any restaurant kitchen. What binds people it seems to me is brokenness, in ways that can show: the barista who runs from the register when she realizes she’s about to be busted for stealing, the fry cook shooting dope in the walk-in, the star chef with a hangover so crushing he chugs three bottles of water as you interview him, then passes out on a 100-pound sack of coffee beans. But mostly people bear the brokenness alone, taking refuge in the distraction that is the punch-list, the visible accomplishment of peeling 60 pounds of shrimp, of baking the genoise cake that can serve as the confectionary embodiment of you, who might be barely able to stand but this cake, with its dusting of powdered sugar, is perfect. And you can do it again tomorrow, you can hide in the repetition, you and your addictions and your loneliness can disappear so long as you hit your marks, beat the choux paste, clean the Hobart, make the kitchen gleam.

Am I making the kitchen sound like a downer? I don’t mean to! I find cooking and especially baking transcendent, the putting together of ingredients until they become this other thing, and I wish I had a video of what happens when I hand-mix a poundcake, the lustrousness of butter-sugar-eggs-flour-vanilla becoming another property entirety, but tonight we will make due instead with guacamole.

Charlie Quintana gave me the recipe when our daughters were little. We picked dozens of avocados off the tree in my yard in Hollywood and made a giant bowl of it for a Christmas party. Charlie was a bona fide a rock star - here he is on drums with Dylan on “Late Night with David Letterman” - and while he struggled with addiction, and died several years ago in Mexico, for a long time he cooked every night for the family he would eventually disappear from.

A variation on the breakage: At Fred Segal, I was asked to train a kid that had just escaped the war in El Salvador. He was maybe 19 and one of the sharpest people I’ve met, fast, funny, asking all the right questions and only needing to be shown things once. A few days in he asked, “You have kids?” No, I told him, that my boyfriend and I were waiting.

“Waiting for what?” he said.

Huh.

He never talked about any hardships he’d been through, but others in the kitchen who’d made the trip with him seemed to, or maybe I am imagining that travel scenario. What I am saying is that they could show up with no papers, no diploma, no training, and Shane and all the other Shanes of the world would and will hire them, will envelop them into the kitchen. Did you know that eggs are considered a binding ingredient? I don’t know how much more metaphorical mothership we get than that, except to say that feeding people is an act of love, you will never convince me otherwise, and even if you are flipping hash browns at Denny’s, you are engaging in the communion of putting food into another human being.

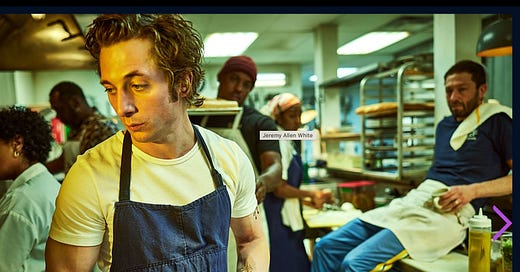

Things get very very messy in “The Bear,” each character breaking all the time, a fighting army of the walking wounded, and while I absolutely understand that Carmy, the lead character played by Jeremy Allen White, is the one, as my daughter said, “everyone is talking about,” I will tell you it’s Richie I am here for, that actor Ebon Moss-Bachrach is crushing my heart with each episode, thow I want to press my fingertips gently on his eye-bags, which seem in particular to be speaking to me, and that his being on the phone in season 1’s finale, “Braciole,” set me crying the rest of the episode.

I stopped working in kitchens soon after my daughter was born, eleven months after the “waiting for what?” question. When she was about three, I received a phone call. It was Michael, the former owner of the company I’d catered for after the baking job, a previously kind of preppy guy from Boston whom, I’d heard, had started using coke, had fucked one of the kitchen staff, had lost his business and his marriage and was now on the phone begging me to help him; he was catering some TV show and could I maybe show up, he was in terrible shape, financially, physically…

“Nancy, I’m bleeding out of my cock,” he said.

I looked at my daughter. We had our day planned, I had an assignment due; I couldn’t come cook, I told Michael, maybe there was something else I could do to help? He made only a yowling sound before hanging up.

I have read zero about “The Bear” and have no idea whether the shows’s creator and director Christopher Storer knows anything about working in a kitchen, but he understands, boy does he, how the kitchen is a beacon, a place of last resort, a place to try anew, how regeneration is baked into the code of the kitchen. You can sling beef sandwiches or be chef at the greatest restaurant in the world — Carmy in fact does both — you can come with nothing and we will let you in, we will feed you, we are nothing without you.

Someone very close to me has often said, “Cooking is a way of showing affection without showing actual affection.”

You’re the only other person I’ve ever heard put this into words, although in a different way.

The Bear has been “picked up” for a second season.

“Did you know that eggs are considered a binding ingredient? I don’t know how much more metaphorical mothership we get than that, except to say that feeding people is an act of love, you will never convince me otherwise...”

Beautifully put. I’ve been cooking more since covid started, and it’s now one of my most favorite things to do.