The Last Christmas

Christmas 1989: I am in New York City with my two-month-old daughter, whom I decide to bring with me when I visit my 85-year-old great-aunt in Mother Cabrini Medical Center, then on East 19th Street. I’d occasionally visited Alice over the years, sneaking an airline-size bottle of booze once or twice as well as dried Italian sausages from Ottomanelli on Bleecker Street, near where Alice Canevari grew up, one of six sisters (and one brother). Alice was legendarily foul-mouthed, apparently shouting out car windows in the 1930s “You dirty ______ bastard!” [insert racial identity of your choice]. Now she was another of the warehoused elderly, if still feisty - she and a male patient tied the knot while lying in their hospital beds, a story that ran in the local papers.

When the elevator doors opened on Christmas Day on Alice’s floor, I was immediately faced with five or six female residents in hospital gowns. They saw me, saw the baby in my arms, and as one began an urgent sort of moan, a moan that turned into a cyclonic howl as they all began reaching toward the baby, patting the air around her, their voices rising wordlessly with the exception, perhaps, of “Baby! Baby!” These women no longer had agency over much of anything, but their primal responses were still their own, and a baby, which they had not likely seen in the flesh in years, triggered something imperative and good. I understood this immediately, albeit it was a bit physically frightening, with Tafv’s dad having to gently protect his daughter’s head and move us on to see Alice.

Spring 1993: Tafv is three, and the possessor of many baby dolls, including the Magic Eating Baby, thus named because I have, for several months, been having the baby “eat” when Tafv is not looking. We do this at the breakfast table. The Magic Eating Baby delights Tafv, who sometimes squeals, “Is she really eating?!” Neither of us really want the game to end, which it inevitably will, and soon, as Tafv by necessity grasps the ways the world works and develops agency.

Christmas 2019: My father has been moved from his assisted living apartment into what is little more than a hospital room at the same facility. This, because he falls a lot - at six-foot five-and-a-half-inches, it’s a long fall - and because he’s basically become disinterested in living. One afternoon when I visit him, he holds my wrist and stares utterly captivated at my watch for 20 minutes. I finally ask my dad - math-savant, rational and, with the exception of opera and maybe Kodak commercials, entirely unsentimental - if he thinks he’s between this world and the next one. He thinks for a minute. “I think so, yes,” he says. A few days later Tafv and I visit. From his hospital bed, my hyper-rational father begins to beam, his smile so big and his eyes so bright that Tavie and I feel as though we are being shot through with light. It makes us laugh, to see him so innocently happy to see us. He has not experienced dementia, but this day I can see how his facilities have shrunk, life and what he’s responsible for and responsive to are now simple. Later, as Tavie and I leave, he gives us the same high beam smile, an instance she and I will recall after his death six weeks later.

January 2023: Mom has been exhibiting signs of dementia for several years. It’s a slow process, hitting her mentally before it does physically, until recently she was go go go. But too many scary incidents - driving on the wrong side of the road, leaving the stove on - have necessitated that she have at least part-time companionship at home and, several days after the new year, that I have her seen by a neurologist in order to protect her from predators and thieves. The assessment - that she is no longer capable of handling her affairs - surprises no one. That same day, I go online and buy her an animatronic cat, which she winds up absolutely adoring, having my daughter and I sit with her as she tries to feed Kitty bits of ham.

February 2024: Four local women now look in on my mom, she is alone only when she sleeps. One arrives one morning to find Mom has fallen, she has broken her hip. I head to the hospital, where the doctor tells me my mother will need a hip replacement or she will never walk again. She has the surgery and, as we will soon realize, will never walk again regardless. She enters a series of rehabs. One is quite nice, a floor made up with what seems to be exclusively Alzheimer’s patients. Across from the elevator is the room of a woman whose wheelchair is positioned in front of the TV, which she does not watch, occupied as she is with holding a naked baby doll, holding it in the air and also by the foot and speaking to it in German sing-song. Other patients gather in the common area, including a woman who’s always dressed impeccably, with her lipstick done. I compliment her on looking so lovely, and she’s both taken aback and flattered, and do I know her son, can I call him, she doesn’t know why she’s here, she will be going home the next day, yes? Mostly I sit with my mom, who is sweet and quiet, much quieter than she was for all the time anyone has known her. At her bedside in June, with Kitty at her feet, I write “The Slow Leave Taking: On Watching My Mother Slip Away,” which reads in part:

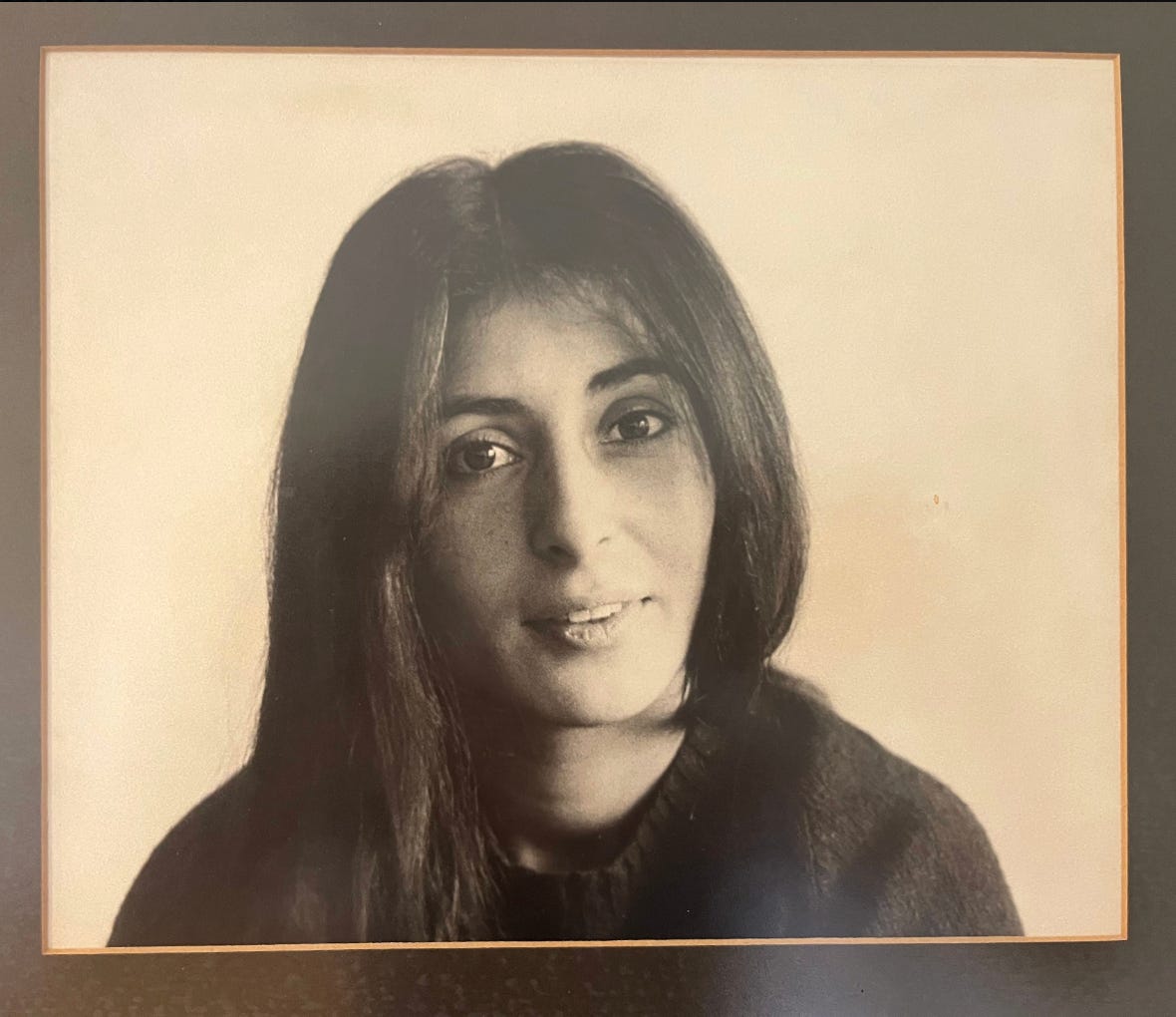

What else can I tell you about my mother? That the only picture she carries in her purse is one of herself. That the orange VW bug she drove us around in as kids had a bike rack and a ski rack and a bumper sticker that read, “Lacrosse: The Fastest Game on Two Feet.” That she used to wake up my brother and me by singing, “Everybody was kung fu fighting!” That when she walked, which she can no longer do, it was faster than any of us, she was ever in motion; even when she slept, she rocked and rocked and woke up in the mornings with her hair all ruched on one side. She also talked so fast that my father said, if he weren’t around her for a few weeks, he couldn’t understand her; that he could not keep up.

What sentences my mother starts now usually trail off. She does not seem bothered by this. We are past the being bothered years, the taking mom’s word for things years, the hiding the car keys and then disconnecting the battery years, the calling the oil company to see if I can wrest back some the excess $11,000 mom has sent, mailing check after check in an attempt to stay on top of her bills. It brings me no joy to see the fight gone out of her, while understanding, it makes it easier, in some ways, for the rest of us.

June - December 2024: Mom comes home. She cannot do anything for herself and, because she has made some sound financial decisions, there is money to pay for 24/7 care. She is assessed by hospice and determined to have less than six months to live. The holidays come and we all say to one another, “It’s her last Christmas for sure.”

Christmas 2025: “Do you think Nana would like this?” I ask Tafv, showing her a baby doll on Amazon. I am hesitant to get it, the doll signaling something to me, maybe, that Mom has lost the facility to know this is not a real baby, though does this matter? She liked the cat…

“Get it,” says Tafv. It arrives on Christmas Eve. Tafv and I bring it to Mom in the morning. She immediately holds the doll, balancing it for 20 minutes, smiling at it, holding her hand.

“What’s her name, Nana?” Tafv asks, a question Mom does not register, she’s busy looking at the doll, and the birds at the feeder in the window. I suggest something to do with Christmas, maybe Mary, or Christy…

Tafv has a better idea. “How about Merry?”

Thank you Nancy. This so loving❤️. What a thoughtful gift- the photo looks as if she is recognizing our most fundamental essence. I hope you all had a wonderful Christmas. 🥧

Such a wonderful share. Thank you so much Nancy. I'm enjoying spending the day with my mom and reading this adds depth to it. Wonderful how words contain multitudes.