In September 1973, my mom asked my dad to leave. We’d moved, the month before, from a small 2-bedroom apartment on Hicks and Pierrepont in Brooklyn Heights, one block east, to Henry and Pierrepont. The new apartment, on the 7th floor, had eight big rooms and wrapped around the corner. One side faced west toward the East River, the other south, with a smack-on view of the Verrazano Bridge. My dad had grown up barely working-class; his mother was a waitress at Schraftt’s in midtown Manhattan, and his father, before he committed suicide when my dad was three, had been a chicken farmer. But my dad was smart, very. He skipped two grades at Our Lady of Pompeii in the West Village, and was dean’s list at Fordham, where he also played on the basketball team. He’d had to leave after his freshman year - no money - but he finished up at City College, married by mom, and by the time he was 27, had two kids and was on his way to becoming a partner at the brokerage firm Neuberger Berman. My mom did not work. She was not a spendthrift but did not, my dad would tell me, understand money, and several times recalled how, soon after they were married, he had gotten a charge plate to a department store. He came home from work one day and my mom shows him a new coat. But how? he asked, they didn’t have any money…

“Oh, it didn’t cost anything,” she said. “I charged it!”

Maybe money was an issue in the household. I was too young to know, but I do remember him saying to her, in the new apartment she’d been decorating for a year, that he didn’t understand why she needed that multi-thousand-dollar Italian tile in the kitchen to also run all the way up one wall. It was in that kitchen that my dad got on one knee and gave me my tenth birthday present: a set of tiny gold earrings in the shape of bows that he’d bought at Tiffany’s. I’ll get it out of the way and tell you that, I lost one of the earrings at the beach the following summer and sifted sand until night.

After he left, my dad moved three blocks away, to the corner of Montague and Montague Terrace, a white-brick building across from the entrance to the Promenade. My younger brother and I sometimes spent weekends there, on the pull-out couch in the living-room. I was taking a cooking class at the time, in the brownstone kitchen of a woman who one evening a week taught six little girls to cook. I took the homemade fettucine I made and put it in my dad’s freezer, in case he got hungry. A few years later, I started neatening his apartment for pocket money. I was there one afternoon cleaning when there was a shimmy in the air, then some noise outside. A woman several floors above me had jumped. By the time I got to the street, someone was covering her, but I could see, she was wearing only a white slip.

The kitchen in my dad’s apartment was very narrow, the appliances on one wall and two narrow shelves on the other. Here, my dad kept what I guess was the everyday booze — Fleischmann’s vodka, Tanqueray, Dubonnet on the top shelf, and below that, two very neat stacks of season tickets, to the Knicks and also, for the first time, the Nets, because of Dr. J. My dad was a basketball freak who would regularly fly to nearby cities to see the Knicks play. When Dr. J was traded to the Sixers in 1976, my dad tore up the Nets tickets.

That same year, something else was on the shelf, a 7”x10” catalog that had been sent by Bloomingdale’s. I don’t think my father ever shopped there, but my mom still had the charge plates and, because he paid the bills, I guess the catalog came to him.

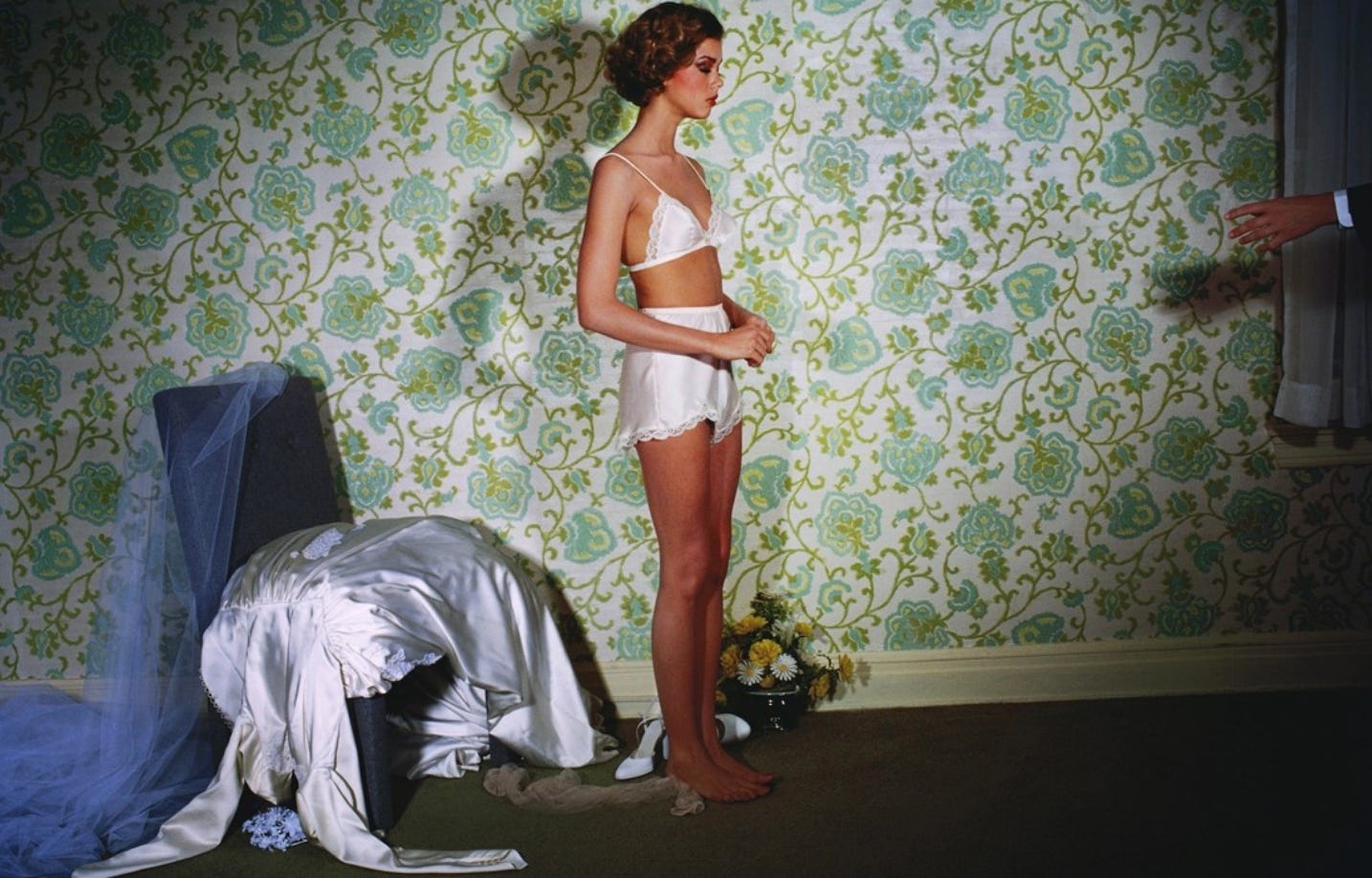

The catalog was, it turned out, a 34-page ad for lingerie. I am sure there was some copy indicating prices and such. I remember none of it. I remember looking and looking and looking and looking. Where were they? Were they in a haunted house? Was it real? It felt real, and then this little trick happened, where I could just open the catalog and be pulled inside it.

I was at an age when I read Glamour and Vogue and Seventeen, and I recognized in the catalog some of the models I saw in magazines, Janice Dickinson and her younger sister, and Lisa Taylor, who I thought of as completely grown-up and sophisticated, based partly on a photo of her looking at a man, which showed me something about what a woman could be, or do, some thing I had not known before.

But in the catalog, she was jumping on a bed!

I must have looked at that catalog 20, 30, 40 times, which was easy to do, as in my memory it stayed on my father’s shelf for at least two years. I have a vague recollection of asking my dad why he kept the catalog so long, and him saying something about the girls being sexy, which they were, but there are a lot of sexy things to look at, exhibit A, the Playboys and Penthouses my dad kept neatly stacked under his bed. Of course I looked through those, too, but they did not have the capacity to spellbind, which is fine! That was not their purpose.

I look at the images now and see, there is spookiness to them; you don’t quite know what’s going on, if the women are in peril or causing the peril.

I remembered the catalog a few years ago and, because my daughter is a photographer, decided to look on eBay and see if I could find a copy for her.

“Oh, Guy Bourdin; I have some of his books,” she said. When I told her, I had not realized the photographer was famous, she gave me a, shocker, Mom look.

A few years before my dad died in 2020, we were in a supermarket. Waiting in the check-out, I noticed him checking out a girl the next line over. She was maybe 22.

“Da-ad,” I said.

“Honey,” he said, “when I stop looking, throw dirt in my eyes.”

My dad would say something similar like "The day I stop looking is the day I am dead." He also made sure to explain to me and my brothers that there is a big difference between looking and leering and I will never forget that.

Weirdly I had a dream about Chris last night (I owe him a call on some Moto Guzzi parts) but also not so weird. He saved my life one night in that enormous apt when I had fallen asleep on the kitchen floor and was apparently choking on vomit. And yet this was the golden era for many of us and I could read an entire book of Rommelmann family history. Didn’t see you much at Remsen Street as you were off to Wesleyan. It was the preeminent man cave of its time and like your catalog offered me respite from the unease and dysfunction of my own home. Funny how these places and things haunt our memories.