Paloma Media Newsletter Week 7

Omicron dropped in for the holidays (thanks a lot!). We're having fun anyway

Hello from the week after last week, which I might characterize as… discombobulated? At least here in NYC, where Omicron stomped in like the unwanted Christmas houseguest and has thus far shown no inclination to get off the couch. Schools are closing (again) and we’re due the season’s first big snow dump. But we also have a new mayor, sworn in right after the ball dropped in Times Square. Jubilation abounded!

We at Paloma Media rang in the new year, as good New Yorkers will, by watching the fireworks from the fire escape and churning out good work! Week 7 saw a remembrance of American painter and caricaturist (and my stepdad) David Levine. Matt Welch and I jumped in the studio to talk about David, Joan Didion and Omicron, illustrated, for reasons that will become clear once you listen, by a pic of a 1990 SoCal pony baseball team (Matt’s the pretty one on the right). We ran New York Post columnist Karol Markowicz’s farewell letter to NYC (and linked our interview with her about the city’s poor Covid response precipitating her move to Florida). And, in conjunction with the new podcast series “Haileywood,” we reran an LA Weekly feature I wrote about the time Bruce Willis romanced and then jilted a small Idaho town.

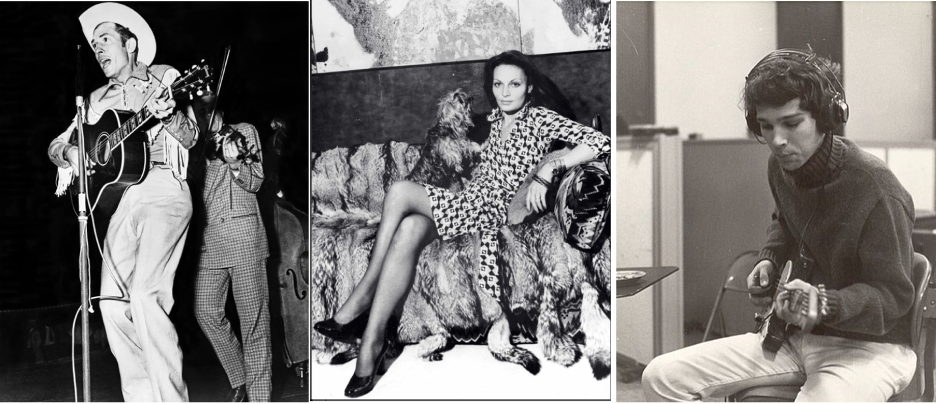

Persons of the Day included Diane von Furstenberg, Hank Williams, Big Star’s Chris Bell, and John Madden, who died last week and whose remembrance, by Scott Ross, begins, "John Madden spent a decade as a raving lunatic..." and which I include below in full, both because we are not (yet!) archiving these and because I don’t think you’ll read better.

We linked Dave Barry’s always great Year in Review, Nigella Lawson whipping up sticky toffee pudding, and one of the best essays of the past few years (which I am going to run again and again until everyone reads it), George Packer’s “The Enemies of Writing.”

The first text of the year I received read, "2022 is going to be fantastic!" I believe it x

John Madden spent a decade as a raving lunatic roaming the sidelines as the incredibly successful head coach of the Oakland Raiders, was one of the most sought-after pitchmen in all of TV land, won a bushel of Emmys for his work as a broadcaster, lent his name one of the most beloved and enduring video game franchises ever, and introduced the world to the culinary monstrosity that is the turkducken. But to fully understand just how large the man loomed not just over the National Football League, but the American consciousness, consider this: there was a time when he was paid more to call NFL games than any single player was played to participate in them. Madden died yesterday at his home in Pleasanton, California. He was 85.

Madden attended Jefferson High School in Daly City, just south of San Francisco, where he was a standout in football. He bounced around a few colleges before sticking at Cal Poly, where he was all-conference as an offensive lineman. Despite a knee injury early in his college career, he was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles, whereupon he promptly injured the other knee, thus ending his pro career before it had really begun. Armed with a Bachelor’s and a Master’s in Education, he was a natural to make the transition to coaching.

Within a few years, he was defensive coordinator at San Diego State University, under Don Coryell, where he caught the eye of Oakland Raiders, who made him their linebackers coach under John Rauch in 1967. During his first year with the team, they won the AFL Championship Game. They would return to the title game in '68, falling to the Jets 27-23, after which, Rauch announced he was taking the top job with the Buffalo Bills. Madden was promoted to the Raiders’ head coaching job at the age of 32, at the time the youngest man ever to hold such a position in the NFL. He proceeded to go on one the greatest ten-year runs the league has ever seen.

A rotund, unkempt man who strained golf shirts and windbreakers to their very limits, Madden was a maniacal presence on the Raiders’ sidelines, flailing and gesticulating wildly while imploring his players and abusing officials with a gusto and volume that was comical for third-party observers, though surely miserable for his victims. During his decade with the team, they went 103-32-7, his .759 winning percentage ranking second in NFL history. The team would make it to five AFL/AFC championship games in his first seven years, losing each time, but it all came together in 1976 with the team going 13-1 in the regular season and then storming through the playoffs to win the franchise’s first Super Bowl.

Madden’s Raiders teams were holy terrors known for their take-no-prisoners defenses exemplified by the likes of Jack “The Assassin” Tatum, while the offense was led by Kenny “The Snake” Stabler, a good-ol’-boy gunslinger who would scramble across hell’s half-acre for as long as it took Hall of Fame receiver Fred Biletnikoff to get open.

Madden decided to hang it up following the 1978 season citing a nasty ulcer and one of sports' first recorded cases of burnout. Madden possessed a uniquely American charm and warmth, combined with an unmatched understanding of the sport and a teacher’s passion for sharing his knowledge, and so wasted no time in sliding into the broadcast booth at CBS, where he eventually teamed up with the Felix to his Oscar, Pat Summerall, a consummate professional who always conveyed the action clearly and with few words as possible.

For a kid growing up in the 1980’s, Sunday afternoons spent with Madden were a blast. Here was a schlumpy goofball who knew everything about football, punctuated the action with the occasional “BAM!” and he made the telestrator a vital part of any broadcast, as he scribbled like a lunatic all over instant replays, diagramming the action and breaking it down.

During this time, he also became a ubiquitous pitchman, making his commercial debut in 1981 mocking his own persona in a spot for Miller Lite. Soon he was schilling for everything from Ace Hardware to “Tough Actin’ Tinactin.” He would go on to rack up all the era’s unofficial accolades of American Celebrity, showing up on The Simpsons, hosting SNL, and appearing in music videos for U2 and Paul Simon. But his greatest and most enduring contribution outside of the broadcast booth came about in 1988, with the release of EA Sports’ Madden NFL, which has so far sold more than a quarter-billion copies, and has spawned the Madden Curse, which has claimed as its victim several of the game’s cover models.

When Rupert Murdoch was still struggling in 1993 to establish Fox as a legitimate network, one of his biggest gambles was to swoop in and buy the NFC broadcast rights out from under CBS. He took along with NFC the duo of Madden and Summerall, and completely reinvented -- for better or worse -- the way sports are broadcast. In 1994, the NFL’s first season on Fox, the San Francisco 49ers’ QB Steve Young was the game’s highest paid player, making $4.5 million—he would lead the team to a title that year, earning the MVP honors for both the regular season and the Super Bowl. John Madden made $8 million.