Let's Talk About Pretendians

Contrary to claims that it's near impossible to determine Native ancestry with any certainty, it's actually very easy: Ask your cousin

“We were at this powwow, and we see this little girl, real real white skin and red-orange braids and she’s out there dancing, just having a good ole time. When she comes off the arena, I ask her, ‘What tribe are you?’ And she goes, ‘I don’t know but Mama knows.’” - Rusty Powell, on the origin story of the Mamaknows tribe

A New Yorker article by Jay Caspian Kang, “A Professor Claimed to Be Native American. Did She Know She Wasn’t?” explores (another) case of a woman claiming to be American Indian and parlaying that cred into a prestigious career at Brown and Columbia. Learning in 2022 that she had no Native blood, Elizabeth Hoover published several statements meant to explain the doggedness with which, at age 42, she tried to determine her lineage.

“I, along with others, conducted genealogical research to verify the tribal descent that my family raised me with, digging through online databases, archival records, and census data.” These searches, she explained, had turned up no evidence of Native American lineage.”

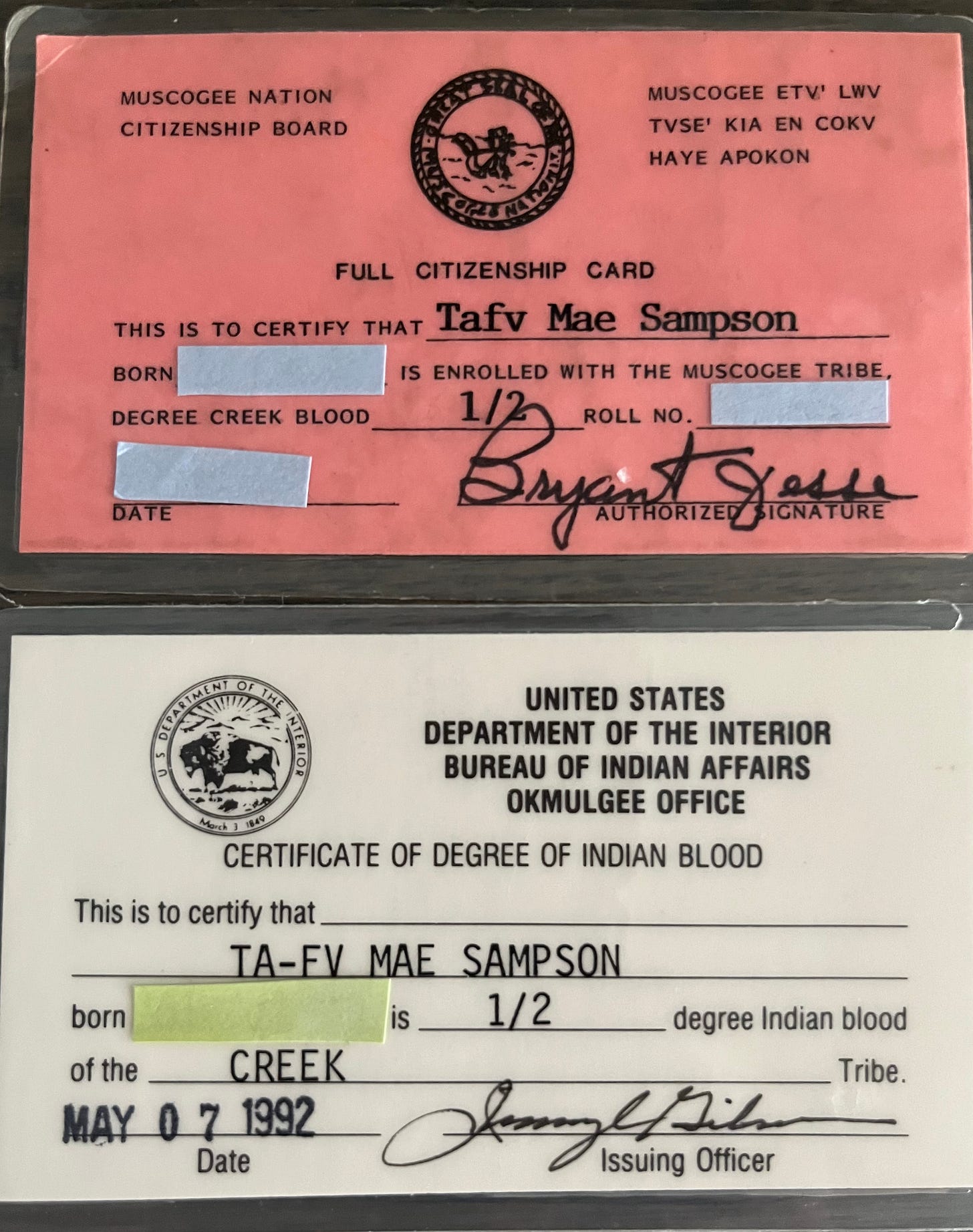

Natives could have saved Hoover the fishing expedition with one question: “Who are your people?” (My late-ex Tim used to refer to Native community as the “moccasin Mafia,” everyone knows everyone or knows their cousin.) That, or have her produce the two pieces of ID nearly all American Indians have, a tribal enrollment card and/or federal Certificate of Indian Blood (CDIB) card. When my daughter was born, you better believe her aunties in Oklahoma (sisters of the above-quoted Rusty Powell), themselves 3/4-Creek (Muscogee), made it their business to get Tafv her enrollment card and to remind Tim, who was full-blood Creek, to get Tafv her CDIB card stat.

Why these are important was something Hoover did not factor in. She leaned instead into the “feeling” of being Indian rather than the realities, one of which is to get doctoring at Indian Health Service clinics and to qualify for various other tribal rights. You need the cards, and if you’re Indian, you’re going to have them.

Hoover did not have them. She also did not have relations, or not beyond being told she had a maternal great-grandmother who was Mohawk Indian and some Mi’kmaq on their father’s side. No cousins, no grandmother, no half-siblings two counties over. Most Indians, particularly on the rez, know who their people are, “cousins by the dozens,” Tim used to say, of the tumble of kids he was raised with in his grandma’s house.

We brought Tafv to Okmulgee the first time when she was 9 months old. Kids, teenagers and adults poured out of Tim’s aunt’s house - next door to grandma’s - to greet us. Twenty more came that night. What I am saying is, you know who your people are. The per capita income ain’t great among Indians, especially on the rez, but people you call family, they have a lot of.

You know what they don’t have a lot of? The need to express their Indian-ness. Hoover had taken the information that her great-grandmother was Mohawk and expanded it over the years to her being of the Mohawk Nation at Kahnawà:ke. This did not sit right with Audra Simpson, an anthropology professor at Columbia and herself a member of the Mohawk Nation at Kahnawà:ke:

Over the years, Simpson occasionally heard about Hoover and spoke with other academics who had noticed the vague way that Hoover talked about her ancestry. Simpson was also slightly suspicious of Hoover on account of the volume of beadwork and Native American signifiers that she was known to wear. (Hoover insists that this is exaggerated, but others described her in a similar fashion. “It looked like an Etsy shop exploded on her,” Simpson said.) On a visit to Kahnawà:ke, Simpson asked around to learn if there was a family named Brooks. There was. “It’s a tiny, tiny family,” Simpson told me. “There were two people still alive.” She asked cousins of the family if Elizabeth Hoover was related to them. “Nobody had ever heard of her,” Simpson said. The next time she saw Hoover, at an American Anthropological Association event, she asked her a direct question: “Who are you?”

It is the case that when we’re kids, we try on different identities. I spent a period of time in my late teens thinking I had Roma (gypsy) ancestry partly because my Czech great-grandmother’s surname - “Luda” or “Louda” - had some tenuous Romany connections, but mostly because I felt out of place in my regular life and wanted to try on another. I think it would’ve been not at all honorable to parlay this into a career, as Hoover did. From the New Yorker piece:

[Brown University colleague Annette] Rodriguez saw a connection between Hoover’s swift rise and how ardently she signaled her supposed Native identity. “I was never in a meeting where she wasn’t beading,” Rodriguez said. “She had different beads in little plastic containers or bags, and she would take them out and start beading during our faculty meetings or when someone was giving a presentation.”

In Rodriguez’s view, Hoover was performing a kind of fantasy of the Native scholar for the non-Native faculty around her—she was what they wanted to see. “She got grants, and she got fellowships, and she checked boxes, and she got positions,” Rodriguez said. “And so she exploited the system. But I think the system also was very happy to have her as the visible Native.”

In other words, Brown was more comfortable with a fake Indian, one who brought the beaded earrings and organized the annual campus powwow, but didn’t carry all the, you know, baggage.

When news broke last October of famed Canadian Native singer Buffy Sainte-Marie actually being an Italian from Massachusetts, Sarah Hepola and I had novelist Sherman Alexie (whose Substack is the bomb) on the Smoke ‘Em If You Got ‘Em podcast (“Sherman Alexie Wants His Scars”). Here he is talking about Prentendians’ habit of romanticizing Indian identity “and turning it into an ATM”…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Make More Pie to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.