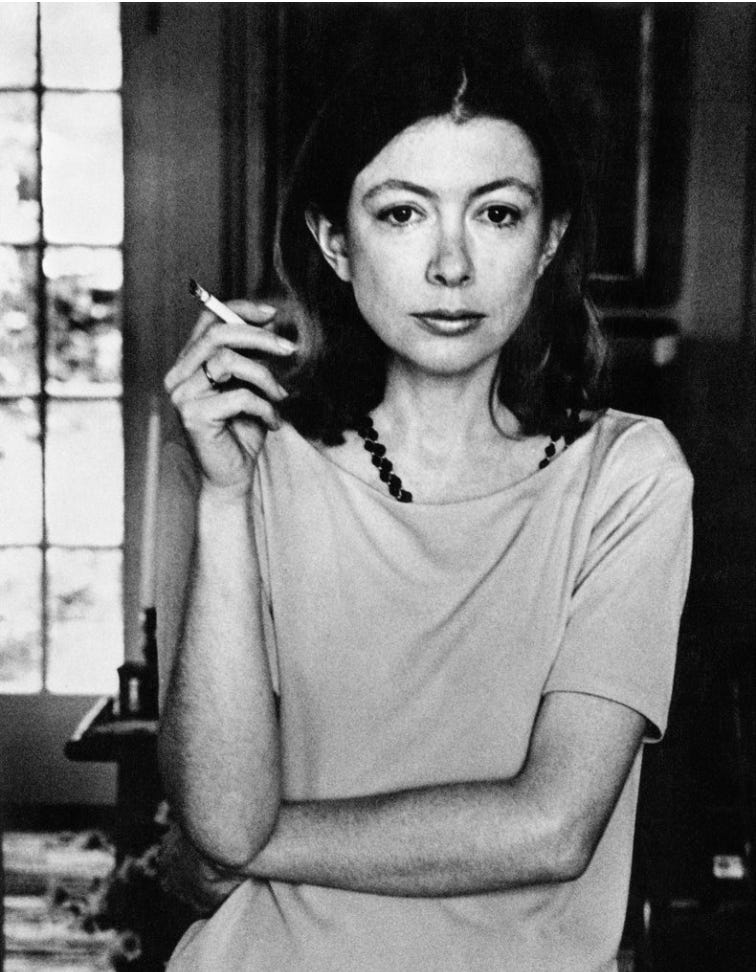

Joan Didion, 1934-2021

I am far from the only writer sitting at her desk weeping at the death of Joan Didion, who as a writer has meant more to me than any, the way she tells you things, the child's longing as she digs what she imagines are her mother's years-old lipstick-stained cigarettes out of the sand; why the Santa Anas make a housewife "calculate how to burn her husband alive in a Volkswagen"; the tropics where you will not get shot, the affair that will go better than you think it will and the one that will not, and the three-year-old boy in the car Didion needed to care for but could not care, and how the need jumped to me. Or that yesterday, I cooked a pot of meat sauce in a large Le Creuset I never use without thinking, Joan Didion had the same one.

It is not an exaggeration to say, I became a writer because of Didion, or more exactly, was told I was a writer. I'd been kicked out of high school at the start of 10th grade for, in the words of the head of school, "turning the school into a brothel and an opium den." An exaggeration, but in any case, eighteen months later I was permitted to reenroll. The head of school was holding a seminar in his office, six students only. For reasons unknown, he allowed me to be one of them. We were assigned Slouching Towards Bethlehem and told to write an essay. I don't recall what I wrote, only that I looked up after reading my essay and he was looking at me with extremely shining eyes. "My god," he said. You're a writer." As if this explained everything.

It is also the case, I am thinking now, that she set me on the path to journalism. Look at her here, reporting from San Francisco 1967-1968, for what would become the pieces in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. I know this position, this stance, exactly, also, how there is no other feeling like getting into the car and driving toward a story you have as yet no way of knowing.

I reread that book a few years ago and wrote to the boy in the car. I wrote it as a birthday gift for Joan Didion, whom I will never stop thanking xx

Dear Michael –

I write to you this morning via someone you knew when you were a very little boy. I do not expect you remember her, though perhaps you remember more from that time than most three year-olds. Habit can create memory, and you had little of that, but so can trauma. Perhaps people told you about the fire and it’s become part of your history, though that would require people to pass along history, and the people you knew then I don’t imagine were around very long. Also, they were people who made a point of not caring about history, they were going to shake off history, history, they said (when they were able to speak; the woman told us you had not as yet), was a burden, a plot.

The woman that knew you then, who sang you “Frère Jacques” in the car, did care about history. She cared about it very much. Caring about history was what brought her to you, to watch history’s destruction, its shredding at the hands of children somewhat older than you and those older still who let go of certain duties, who were soft on themselves and distractible and pretended there would be no cost for this distraction.

Your mother was distracted, though I can see she also had some homing instinct. What speaks more of home than baking bread? She might not have thought of it this way as she formed the dough, which (you may not know) feels very much like a living baby. The woman wrote that she was struck by “how it is possible for people to be the unconscious instruments of values they strenuously reject on a conscious level.”

I have seen, if fifteen years later, what your mother rejected: the 19 year-old in the apartment over the train-tracks in Middletown, a living room/kitchenette of her parents’ castoffs, the infant asleep on the floor, his father stricken in his varsity jacket, “thanks for coming by, guys.” They were people your mother, could she have seen to 1981, might have called square, might have called trapped. They were trapped. It was easy to hear the shriek of time in that apartment, the tick of the clock, too. They were not allowed the soft distractions (her father made sure of that); they put what they learned on its feet, their son would be ten years graduated from the college they were forced to drop out of.

I wonder what happened to you. She wondered, too. She had been alarmed at what perils she saw rush in when the center did not hold, at men who did not after the fire reach for you but instead searched for more forgetfulness beneath the floorboards. Perhaps these men told your mother, “You should be watching that boy.” Perhaps she got you out of there.

The woman, I could tell, wanted to get you out. She had only one way to do this, to introduce us. But maybe too, she was pressing something in your palm that day in the car. Maybe the song was a signal; maybe she was thinking your first words could be, “Mom, the bells are ringing.”