Forty Bucks and A Dream: Stories of Los Angeles. Chapter 13: SANCTUARY: Days and Nights at the King Edward Saloon

I am serializing Forty Bucks and A Dream: Stories of Los Angeles on Substack. New chapters drop Mondays. Below is the Table of Contents, with links to what’s posted before. Eagle-eyed readers will notice I have skipped over Chapter 12. There are reasons. I’ll include it in the printed version and/or send to paid subscribers if that number reaches, appropriately, XXX.

FORTY BUCKS AND A DREAM: Stories of Los Angeles

PROLOGUE

STARLETS

1: Forty Bucks and a Dream: The lives of a Hollywood motel

2: The Camera and the Audience

3: Jena at 15: A childhood in Hollywood

4: The Waxer

LEADING MEN

6: Brown Dirt Cowboys: Meet your Mexican gardening crew

7: Punch Drunk

LEADING LADIES

9: Who She Took With Her: The husband, the son, the boyfriend… a drunk’s tale

11: No Exit Plan: The lies and follies of Laura Albert, a.k.a., J.T. Leroy

12: Porn for Women

BACKGROUND PLAYERS

13: Sanctuary: Days and nights at the King Edward Saloon

14: Why Not to Write About the Supreme Master of the Universe: A day with the disciples of Ching Hai

15: Playboy: The next generation

16: J. Lo in the House

CUT

17: The Marrying Room

18: Meet the Neighbors

19: The Pathos of Failing

20: Bite and Smile

SANCTUARY: Days and nights at the King Edward Saloon

FRIDAY, 2 P.M. LOS ANGELES AND FIFTH STREETS. Shoppers, six deep on the sidewalk, cramming in and out of discount clothing, toy and tool shops, bumping past roast-corn vendors and the indigent, who offer to watch parked cars for a little something, anything at all. Buses and cars and baby strollers race to beat the light, delivery trucks jam up the alley and lay on their horns, people yell and push, so much humanity, too much movement.

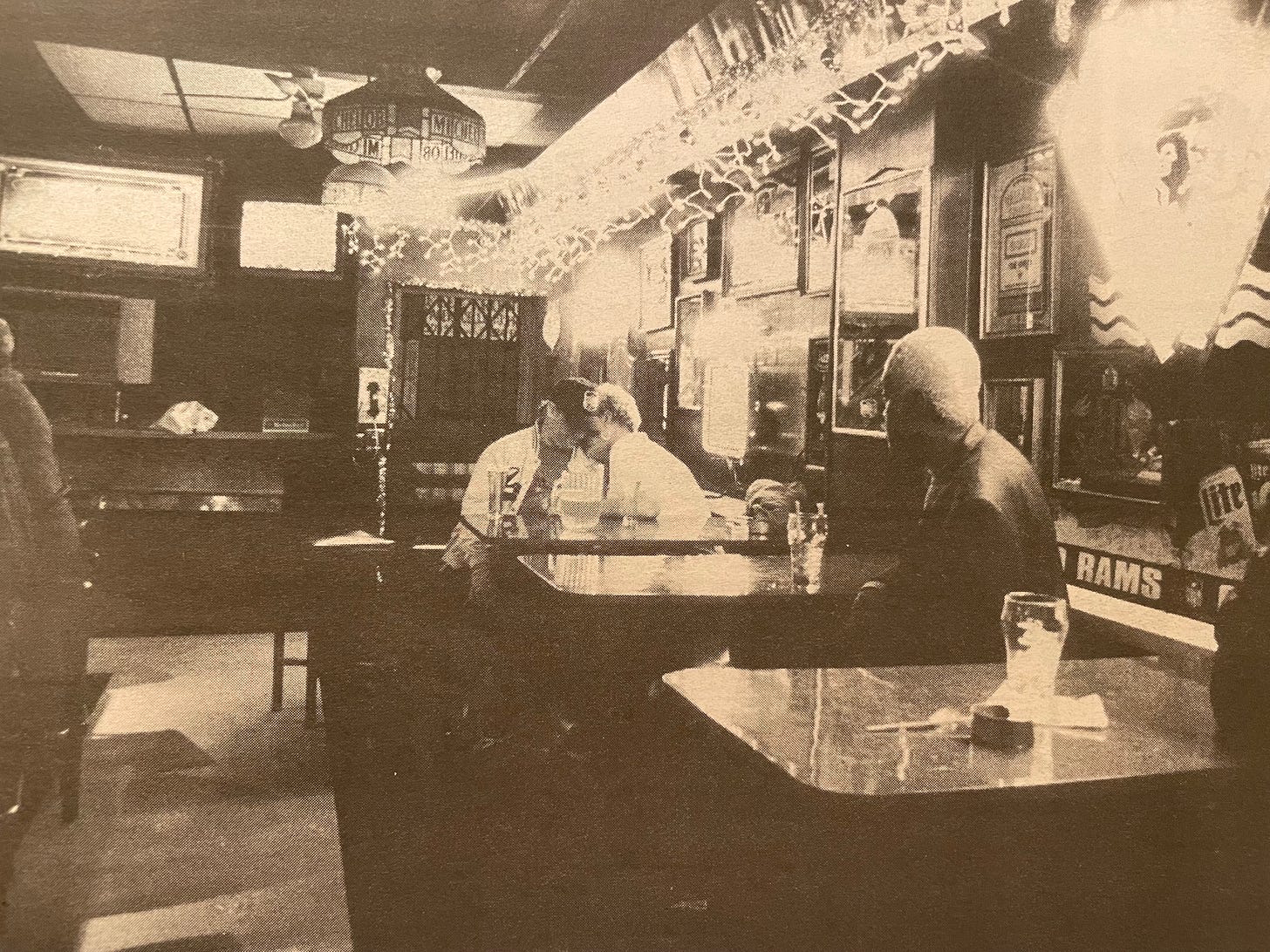

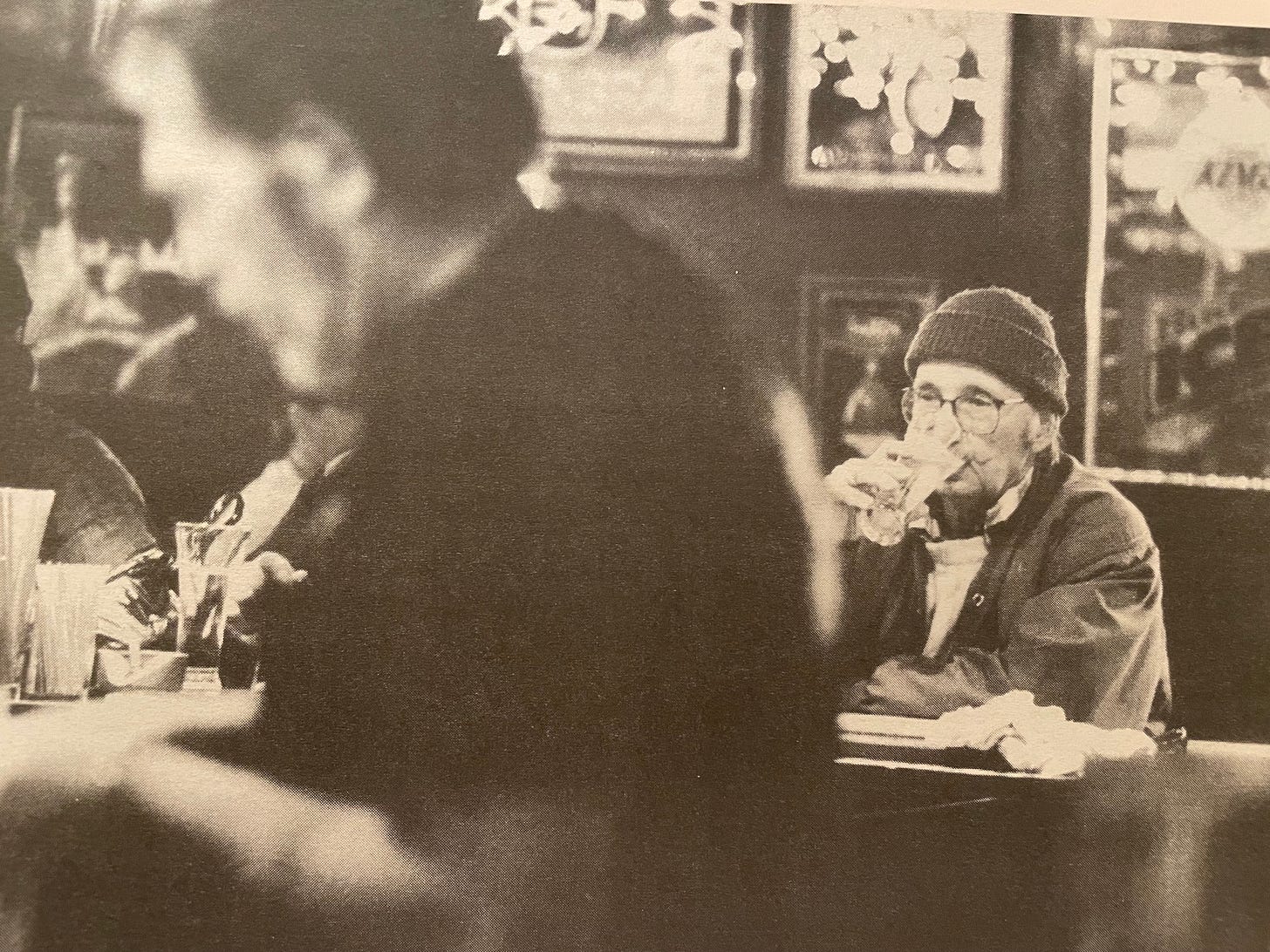

Tune out the picture; turn off the sound. Head into the King Edward Saloon, situated beneath the 110-year-old landmark hotel-turned-SRO the King Edward. Except for the seven muted televisions showing old movies, and a little Roy Orbison on the jukebox, King Eddy's is quiet. The weak light coming through the windows makes it hard to see people's faces. Slowly, one side of the long bar comes into relief. A dozen men, drinking alone or in pairs, sit so silent and still they could be made of wax. There's a bodybuilder gone to fat, a loose tank top showing what were his pecs; a thin African in a dusty blue blazer; a few truckers; a handful of men over sixty with Dust Bowl faces, sunken cheeks and thousand-yard stares.

Take a seat at the other side of the bar, where a livelier group who look as though they might have a few bucks in their pockets, discuss the political situation. Look to the short end of the bar, where a fifty-year-old woman with a blond bob and the leathery complexion of someone who drinks steadily is animatedly making a point.

“Let me tell you something,” she says, getting off her stool and gesturing broadly to her drinking companion, a portly man who looks amused by her vigor. Catch the attention of the bartender, Jim Hill, who has a Mephistophelean goatee and twinkly eyes.

“Always happy to see a pretty lady,” Jim says, setting up a shot of tequila and a beer back. Two bucks.

“That's on me,” says a seventy-year-old gentleman, making it known he appreciates the company. It's nice to have someone new to tell his story to.

“I live down here now, see,” the gentleman says. He means upstairs, in the King Edward, where a room with a bath runs $266 a month. “I worked forty years, I had a wife. A couple of years ago, she gives me the 'It's the bottle or me' ultimatum,” he says, signaling for another round, letting his hand wander over his new friend's shoulder. “Actually, what she said was, I could stay if I just kept drinking beer.”

He picks up his glass of bourbon and smiles into it. “I made my choice. The house is paid for, she's got a good life, and I have what I want.”

Another round appears, and another, too many to keep up with, flying from all sides of the bar. Any woman under age forty-five cannot buy her own drink at King Eddy's; she could have a hair growing out of the end of her nose and still be cause for celebration.

“It's good to see you. Haven't seen you in a while,” says J.J., a small, dark man who looks as though he'd like to dance to the Harry James tune that's just come on. J.J.'s 55 if he's a day, he's alone, he has nothing to lose. “Yes,” he says. “I want you so much.”

Try to make it to the bathroom, at the far, dark end of the room, where a group of regulars who don't appear to speak English sit for hours at a stretch. On the bar in front of them is the key to the ladies' room, attached to a wooden dowel. One of them hands off the key as soon as a woman in need appears. It's a generous, wordless gesture, transacted with the winks and smiles and little laughs that, to the inebriated, speak volumes.

Exit the bathroom. “You don't love me anymore,” J.J. says, looking dejected. A middle-aged woman near him suggests a comeback to that particular line.

“When someone says that to you, say, 'I don't love you any less,'“ she says. Her voice is sandy. It's a good line.

“At least I'm good for something,” she says.

Go back to the well-lit side of the bar. Continue a conversation with bartender Jim, who lives upstairs but is originally from Texas, and has a few choice words about the Bush boys, “whose daddy bailed them out of everything they ever done.” Two minutes later, the advice lady is back. One eye and cheek are puffed up and tender, and a tube pokes from beneath the bandages around her throat.

“Now, if anyone says to you, 'Had enough?' you say, 'I never have enough.'“ She stands mute for a few seconds, then walks back to her stool.

Stay until dark. Exit onto a scene the opposite of earlier in the day: a completely empty street, except for the homeless setting up their tents and boxes.

FRIDAY, 7 P.M. “HEY, BILL,” SAYS LIZ, RACING INTO King Eddy's like a spark, her waffle-weave shirt reading The Bar Feeders, her platinum-and-pink hair rolled into pixie cones.

“Hey, kid,” says manager and bartender Bill Roller, pulling her a draft beer.

An artist and singer for the punk band Tongue, Liz lives around the corner in the Canadian, a building of lofts inhabited mostly by artists. When she drinks, it’s usually at King Eddy’s.

“It's the cleanest bar downtown,” she says. “You can't walk into some places without someone trying to stick a needle in your arm.”

A shabby black guy comes through the door, approaching Liz with a request that doesn't get past his lips before Bill tells him to, “Keep walking, keep walking.” The guy leaves.

“That guy, he's always trying to get you to buy him a beer,” Liz says. “So we buy him a beer one night. Then he asks for money for the jukebox, so we give that to him, and he goes over and plays what he thinks is 'white music,' then he comes back and wants a tip for playing this white music.”

Liz's friend Dez, a guitarist and singer for an early version of Black Flag, arrives. Yes, King Eddy's is their favorite bar, but it's also close and, since neither has a car (Dez has never driven), accessible.

“And it opens at six in the morning,” says Dez, who lives within walking distance.

A few of their pals arrive. They take one of the countertop tables against the far wall.

“First round's taken care of, kids,” Bill says, handing over a pitcher. They haven't been in the bar three minutes. Who paid?

“I seen you in here earlier, and you didn't let me buy you those beers,” says an old-time cowboy, the kind with no ass to hold up his Wranglers, a permanent cigarette in his mouth and a face as cracked as parched mud.

“How about you let us buy you a drink?” Liz says.

“Young lady, you kids will not ever have the kind of money I have,” Cowboy says, and pays for the next round, too, before going back to his buddies, all the while keeping an eye out so not one drop gets drunk that he hasn't paid for.

It's a busy night at King Eddy's. The V.A. checks have come in the day before, so the veterans, who make up a sizable portion of the clientele, are feeling flush. The mood is festive, there's noise and movement from all sides of the room; red, green and yellow party lights give color to the old cheeks.

Cowboy sidles up to Liz and a friend. “You girls want to make $150, $200 an hour?”

“Uh . . . sure,” Liz says, smiling and walking the next round of drinks back to the table.

Seeing the men-folk there, Cowboy pulls up a little short. “How's about all you guys want to work this weekend?”

“What do we have to do?” Dez asks.

“What we're gonna do is, I'll fly you all out to Vegas tomorrow, and you'll work all weekend,” Cowboy says. It's not possible to tell whether he's serious or making this up on the spot. “All you have to do is walk up and down the street, just back and forth, and I'll give you two-hundred-and-fifty dollars each for the day.”

Like extra work?

“Yeah, that's what it is. I make movies, videos. We're about to do another one, in Africa,” Cowboy says, pulling out a business card. “I'm staying out here in my motor home tonight, but I'm leaving tomorrow. Here, take down these numbers.” He rattles off the numbers to his cell, his pager, his office, his mobile. He makes Liz write them on a napkin, then read them back to him. “That's it. You want to do it, you have to call me by eight a.m.”

A few minutes later the napkin falls on the floor, where it's run over by a battery-operated scooter. The woman with the blond bob, who lives in a hotel room across the street, is in high spirits, looking sharp in a black motorcycle jacket and revving her new toy across the floor. When it crashes into Liz's foot for the fifth time, Blondie comes in close and peers into Liz's face.

“She's about twelve!” Blondie shouts.

“It's her twenty-ninth birthday,” Dez says.

Blondie arches her eyebrows as high as they'll go and puts her hands on her hips. “I don't think so,” she scolds, walking to the pay phone on the wall, pretending to alert the authorities to the fact that there are minors drinking at King Eddy's.

“And him,” she squeals, pointing at Liz's friend Din. “He's about nineteen, and oh my god,” she says, making hubba-hubba eyes, “look how handsome.” She begins to moon extravagantly over Din, telling him she's going to take him away from his girlfriend; his girlfriend tells her to give it her best shot, and by the way, what's her name?

“I'll only tell him,” she says, cupping her hand over Din's ear and leaning into him for a solid minute. Blondie stays around for a drink before taking her scooter for a spin on the other side of the bar.

“What was her name, anyway?” Liz asks.

“I don't know,” Din says. “All she did was breathe in my ear.”

SATURDAY, 9 P.M. WINTER AND JIMMY, WHO LIVE ON MAIN and Seventh, come in with their friend Brittany, who has a loft in Bunker Hill but has never been to King Eddy's. Winter designs for Trashy Lingerie, Jimmy's a musician who played with the original Avengers and Chris Isaak's band, and Brittany's a porn star, which is sort of apparent from her enormous tits, though her outfit is comparatively toned down, a pair of faded jeans and a tiny navy midriff.

“More or less, I produce, direct and write pornos,” Brittany says. “Then I have Internet sales. I'm also a porn-star-slash-model and actress. And I give blowjobs for a living.” She laughs like Fran Drescher. How many films has she done?

“Oh, jeepers, it's mostly soft-core, but over four hundred.”

Jimmy leans in and whispers, “Did you get that jeepers?”

“I was raised in Milwaukee, but I have like one friend that lives there who's a Christian with seven kids, and I send her money,” Brittany says. “Along with everybody else in my family.”

She and Winter talk about the exigencies of bleaching their hair blond.

“I'm really a redhead,” Winter says, edging her pants over her hipbones, showing a wisp of orange pubic hair. “This part, I've never waxed, it's my teenage hair. The rest, all around, grows in black, but I leave this virginal.”

She tells Brittany about a new look she's been doing. “First thing you gotta do is come up with your cholita name -- mine's Chuchi Loca. Then you go get yourself a gold necklace with the name in script. Then you get white eye shadow. Then we go to all these foofy fucking clubs in Hollywood, and say, 'Fuck you. What are you looking at?' It's all about the wife-beater and the Dickies hanging down and your thong hanging out. It's all about the Snoop Dogg thang.”

“I got big tits, so I gotta do something with the tits,” Brittany says.

“It's not a gangbanger look, it's a little hometown, a little Hollywood. Oh, and nails -- nails are big. And tattoos. The best tattoos are the ones you get from the supermarket vending machines. 'Laugh Now, Cry Later.' Or you get your boyfriend's name tattooed across your neck.”

“Or around your asshole. 'Property of Big Bob.'“

“Believe it or not, I've never done it in the ass,” Winter says.

“Man, I get raped in the ass for hours,” Brittany says. “Seymour Butts, this porn producer who does all anal, his girls get 'Seymour Butts' tattooed across their asses.”

“At Trashy, I made so many dresses for this bitch that had to have the ass cut out so you could see her tattoo, 'Property of Seymour Butts,'“ Winter says.

Back to the breasts: Brittany doesn't like hers. She was twenty when she had them done and they're too big.

“I have to spend twenty thousand to have them redone,” she says. “They're so huge, they're four inches lower than they're supposed to be. They're bigger than my fucking head. I don't have any scars because they did it through my belly button, but to reduce them they have to take off my nipples. I fucking hate them. They're too big.”

She leans over and lets them drop out of her top: At this angle, they look nice and smooth. Tan.

“I just want to go down to a D,” she says. “I don't want small tits, I'm used to them big.”

“You have saline or silicone?” Winter asks.

“Saline.”

“I'm going to get silicone, silicone doesn't ripple,” Winter says. “I'm thirty, and they just don't have the oomph they used to.”

The acquaintance sitting with them mentions she'd never have hers done, that they seem to be hanging in there.

“Let's see,” Winter and Brittany say. The girl lifts her shirt and bra and shows the girls, and the entire right side of the bar in the process. There is no reaction whatsoever from the latter.

Winter cracks up. “You have to love King Eddy's. In five minutes, they've seen four tits and one bush, and no one even blinks.”

MONDAY, 2:30 P.M. A PAPER SIGN TACKED OVER ONE SIDE of the bar reads:

I can only please one person per day

Today is not your day

Tomorrow doesn't look good, either

Anthony is a forty-three-year-old Isleta Indian from New Mexico, living in a hotel room nearby until the money from the sale of his mother's house comes through.

“They sold it six months ago,” Anthony says, pouring the last of a pitcher of beer into his glass. “My brothers and sisters, they're greedy.”

Anthony used to work as a plasterer, before falling off a ladder in Montebello. He's disabled now. “I get six hundred and thirty four dollars a month from Social Security, then I get a check from insurance.”

This does not mean he is not going to work. He has a calling.

“I went to UCLA for ten years, studied business. I have a business credential,” he says, wiping beer off his long mustache. “I'm gonna read the pyramids, for the Library of Congress. I hope. I need at least ten credentials to read the pyramids, otherwise it will be a fallacy . . . I'm talking about the pyramids in Mexico. There's a section down there called the Blue Lagoon, right outside Guatemala, where the Incas were. I have an ability. If you look at a dollar bill, at the eye of the mesa: that's a shrine. The belief in tomorrow.”

At the end of the bar is a guy who looks disarmingly like former Major League Baseball player Darryl Strawberry; he's even wearing a Yankees cap. “The eye is Egyptian,” the guy shouts.

“It's Shriner. It's Mason,” Anthony shouts back.

“It's not Inca, it's Egyptian!”

“It's Shriner, don't tell me, what the fuck, I belong to the church.”

Anthony goes to the bathroom. Darryl (who says his name is “none of your fucking business”) shouts after him. “That eye has nothing to do with the Incas, you know it and I know it. That's Egyptian!”

When Anthony is out of earshot, Darryl says, “Everybody is so fucking smart. It's the L.A. water. These are the people who piss and shit on your streets. There wasn't an Inca around when they made that dollar bill.” He launches into a caustic monologue about the superiority of New York over L.A.

“That eye belongs to Morton Salt, from Utah,” Anthony says, back on his stool and ordering another pitcher. “He's the head of the Mason Church. It's a secret society. The first president was George Washington.”

“I'm sorry to interrupt,” Darryl says, not sorry to interrupt as he sticks his face in front of Anthony's, “but he doesn't know New York is better because he's never been there. Look outside, you see that? In L.A., two sides of the street are like one side of the street in New York. Two sides like one!”

Freddy Fender singing, “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” comes on the jukebox. Darryl stomps back to his stool and, every five seconds or so, shouts something about the Bronx, about Manhattan.

“In Mason, they believe in Satan, Satan is the redeemer. I'm a Mason,” Anthony says. “I can go to court right now and get out, only because I'm a Mason. All judges are Mason. It's a very, very strong society. They're also called Shriners. To become a Shriner you have to go to the fifty-eighth category. That means you're above all levels of the law, you're on the level of God. I know Satan, I'm a Shriner myself.”

“Shriners are fucking Polacks,” Darryl says, and walks out of the bar.

Anthony talks about what he'll do at the pyramids. “They have you read hieroglyphics and come up with an interpretation. [The Incas] believed in extraterrestrials. So what I'm doing is, I have a girl named Yaqui, she's about eighteen inches tall and she's green. She'll contact you.”

A Native American woman with a mullet and a black lurex blouse helps an old man in a walker around the bar and toward a seat by the open front door. It's a pretty day outside.

“And I'm expecting some income from the Veterans Administration,” Anthony says. “I went to Vietnam, in 1970. I was there nine months and twenty-one days. In Hemp Ho. H-E-M-P H-O. I was in the Marines. I played in a band, too. Guitar and piano, too. I wrote my first song when I was sixteen.”

Can he sing it?

He closes his eyes and makes his hands play the chords, stops, tries again. He smiles as though he's genuinely surprised. “I can't remember the words.”

Forty minutes after she started, the Native woman has yet to get the old man comfortably into his seat. Bill comes from around the bar to help

FRIDAY, 8:30 P.M. IT'S COLD OUTSIDE. LOOK FOR A parking spot close by King Eddy's, where the car can be seen from inside. This is easy, as the street is empty. It always is after dark, though one block east a hundred people jostle for food in front of the Midnight Mission. And on the corner of Fourth, half as many agitate a few feet in one direction, then back; it's impossible to see what, if anything, is making them move like a mass of seaweed.

Inside King Eddy's, it's warm and bright. A Man Called Horse plays on the TV, Richard Harris looking blond and fey amid the swarthy villains and the Native children, who walk off-camera giggling after flogging Harris with sticks. The Native woman with a mullet has added large pearl earrings to her ensemble, and is lip-synching to “kiss me once then kiss me twice then kiss me once again,” her eyes closing dreamily during the sax solo.

“You'll be more comfortable sitting there,” Bill says, indicating a stool farther away from a few drinkers who look as though they've had a long head start.

“Hey, have you young folks ever been to Burbank?” asks a jumpy gentleman in a jogging outfit. “I was driving over there the other day, and this officer stops me. I ask him, 'What's wrong? Did I run a red light? Am I speeding?' He says, 'No. You're going the wrong way down a one-way street!'“ Burbank cackles. Bill is standing behind the bar with his arms crossed, his forbearance thin. Burbank knows it, but what the hell.

“Hey, did you kids . . .”

“Move along,” Bill says, waving Burbank back from whence he came, on the other side of the bar, with the daytime regulars.

Liz comes in. She and her friend Joe have been putting in twenty-hour days for Fox Sports.

“How you doing, kid?” Bill asks.

“Good, good, exhausted,” Liz says.

“Listen, I'll be happy to hang some paintings by the kids from the loft,” Bill says, tapping a beer. “Tell 'em to put a price on them and I'll hang them up. But not too pornographic.”

“Cool,” Liz says. “We've been installing fiber optics into these mini stadiums, Fenway Park, Daytona. Fiber optics sounds so cool, but it's like fishing line.”

“The stadiums are made by the Danbury Mint,” Joe says. “Which is like the bastard Franklin Mint.”

Burbank comes back with an expectant smile, holding a deck of cards.

“No cards on the bar,” Bill tells him.

“I'm not going to open them up, okay? I'm just going to tell them how it's done.” Burbank niggles his way in, pushing Liz off her stool. “This trick is called 'Immaculate Conception.' You take a card, then I tell you what it is, then you take another card, and I…”

“No cards at the bar, I already told you that,” Bill says.

“But I'm just telling them.”

“Move. Go,” Bill says. Burbank goes.

Liz orders a $3 plate of eggs, hash browns and sausage covered in white gravy, a plate big enough for a trucker, and eats it at the bar.

“You got the munchies, kid?” Bill asks.

“I haven't had dinner.”

“That's not dinner, that's breakfast.”

“I haven't had breakfast yet, either.”

Johnny Cash comes on, singing “Folsom Prison Blues.”

“When I was at the girls' home, in San Diego, I used to have to make this every Sunday,” Liz says, and that she’s from Altadena by way of a few places her parents shipped her off to.

A pretty woman named Suze, who used to bartend at King Eddy's and now lives upstairs, comes in wearing a blue satin baseball jacket and waving an article about the bar that appeared in the Downtown News. She shows it to Liz, who's quoted as saying, “It's a place to be.”

“Did I say that?” Liz says, laughing and grimacing at the same time.

Suze makes the assembled read the piece, headlined “No Martinis Here,” in which the writer calls King Eddy's “a watering hole for war veterans, alcoholics and druggies . . . this won't make the pages of Esquire.” After a few drinks, the writer said she headed fearfully for her car, thinking, “It's a long drive home to Beverly Hills. In more ways than one.”

“Can you believe it?” Suze asks.

“We're not Beverly Hills,” Bill says. “You want to spend sixteen dollars for a round of drinks, go to Beverly Hills, you don't belong around here.”

Everyone here likes King Eddy's the way it is, likes downtown the way it is; they don't like the rumors and realities of change. The topic of the real estate developer Tom Gilmore, who's been gutting old bank buildings and turning them into lofts, quickly becomes rancorous.

“My rent's going to go from like three-hundred-and-forty a month to eighteen million,” Liz says. “I guess we're spoiled, the prices are so cheap. My view is probably pretty twisted, I like my life and I don't want it to change. I've been here eight years and, especially in the last two years, I've loved it, I don't want it to change. Perfect.”

It's 11:30, closing time. Liz and Joe tip Bill extravagantly, tucking money into the neck of his T-shirt. He pantomimes a cancan dancer, lifting his apron and batting his eyes; at sixty-two, he still manages to look like the Marine he was. Get ready to leave.

“Anytime you're here and you're by yourself, just say something, and I'll walk you to your car,” bartender Jim Hill says.

It's very dark along Los Angeles Street, with streetlights out or never installed. The brightest light comes from the new Rosslyn Hotel sign, formerly made of bulbs, newly rendered in LED lights in primary colors, red blue and yellow light blasting down Fifth Street, pooling over the sleepers and wanderers, and on the Gilmore Associates leasing office at the corner of Fourth and Main.

SATURDAY, 12:30 P.M. “LOOK AT THIS,” SAYS BILL, TAKING A cigarette break in front of King Eddy's and nodding at the throng of Saturday shoppers. “Is this scary? No.”

He's still rankled about the article. “Just because we're on the edge of Skid Row doesn't mean we're a Skid Row bar,” he says. “This used to be a workingman's bar. Only have one labor pool left in this neighborhood, Crest, over on Fifth, great bunch of guys. They come in, cash their checks; have a few drinks. We used to have nineteen [labor pools] down here. We used to have Broadway before it folded up years ago. We used to have nineteen bars between here and Central. Now, there are four bars in the downtown area. You got Cole's, Craby Joe's, Charlie O's and this place.”

He stands back from the doorway so a man in a wheelchair and holding his tank of oxygen in his lap can pass. Because he can't get up to the bar itself, Jim Hill, who's on break, orders the guy what he wants, a pack of Marlboro Lights.

“The majority of my clientele are permanent,” Bill says. “Every one of them here lives in one of these hotels, a couple of them live on the Westside, they always stop in here, you know, they feel comfortable. When they're ready to go, we call a cab, and they go home. Night-crowd people who work all week come and relax a little bit. Like the kids, they work all day, they do their thing, they come in here, blow a little steam. They're not rowdy. We won't let a rowdy crowd in. We ask them to leave. They don't leave, we pick up the phone and have an escort get them out of here.”

Bill rents two rooms upstairs, for his girlfriend and himself, $500 total. He can afford it. Most people at King Eddy's have a hard time paying for one room. “They're living on Social Security, or SSI, so they just have to budget themselves to make ends meet. If you come down to the street . . .”

He takes a second to size up his visitor, and then says, “You're a gutsy little gal, try this: Get yourself eight hundred dollars and the clothes on your back, and live on the street for one month. Live in this hotel for one month. Now, out of that eight hundred, you gotta pay your rent; buy your groceries; you want a TV, you have to buy that; you want a microwave, you have to buy that. Let's see how far you last on eight hundred dollars, without touching your bank account, without calling your sister up and saying, 'Help.' And you want to come and have a drink, because you need some kind of social life. Try it. I dare you.”

Blondie's on the far side of the bar today, not looking too well. It's the end of the month. Money's tight. Social Security and general relief checks don't come until the beginning of the month.

“Majority of them are single people, a few of them are married couples, trying to get back on their feet again,” Bill says. “They stay here for two, three months, before they get their finances built up, their job organized, then they move where it's comfortable for them. But once they're stuck down here, unless they're really motivated to do something to get out of here, they're going to be stuck. A lot of people accept it, they accept their environment, but they're not down here because of choice, they're down here because of economics.”

This is the main reason Bill keeps prices low. “I have a meatloaf sandwich up there, three dollars,” he says, pointing to the grill menu. “They go a block and a half, meatloaf sandwich, seven seventy-five. At Cole's, seven seventy-five. So they come in here for something reasonable to eat. We make them a good sandwich; we don't gouge them. That's all I can say about it, really. We try to look out for our people . . . It's a workingman's bar and retired people's bar, and it's a nice bar. Regular man's bar. We have sports on TV, we have seven TVs; we can get almost every game going. We can't get the [Lewis-Tua] fight, we're not gonna pay. It costs you fifty dollars at home, but it's three hundred dollars for a bar, then you have to charge, and these people can't afford it. 'Hey, you wanna watch the fight, it's gonna cost you ten bucks.' I'm not gonna do it. I'm not gonna do it. I don't need tricks, it works the way it is, I don't need no tricks to get my clients . . . We run a clean bar, clean food, we don't allow too many bad influences coming in the bar. I won't even let them come in here and panhandle a cigarette.”

Bill throws his own out into the street. He's been working and living downtown, on and off, going on twenty-seven years.

“I remember, back in the old days, this place was booming, okay. The labor pool was sending out four hundred, five hundred guys. If you couldn't get a job down here, there was something wrong with you. Long as you go in there with clean hands, you get a job, and this bar was packed every day, strictly working-class. Now, they bought up all this toy district and everything else . . . you can see the difference, you can see the difference. I seen lawyers go belly-up, okay, I seen them on the street, turned into complete alcoholics until one of their in-laws came down and grabbed 'em by the scruff of the neck and took 'em home and cleaned 'em up. But everybody has to start someplace, and this is the lowest rent you can get, period. Let's face it, this is the lowest-rent district.”

FRIDAY, 8 P.M. AN OLD WOMAN WHO HAS BEEN SITTING by herself at a countertop table comes slowly around the bar, leaning heavily on her cane. Her fist looks frail as it hovers over the bar. She opens her hand: A crumpled one and two quarters fall out.

“Buy you a beer?” she asks in a small, sweet voice. She's less than five feet tall, with a heart-shaped face shadowed by what was likely great beauty.

How about someone buys her a beer? She stares coquettishly, nods, collects her money and goes back to her table.

Is she here alone?

“Little Honeybun?” Bill asks. “She's lonely because her boyfriend went home early, and she just don't want to go home.”

Jeremy's lonely tonight, too. In his twenties, sporting a plaid wool cap and wiry muttonchops, he lives in the Canadian and is part of a band called Syncopation (“at the moment”) that's playing later that night at the Smell. Right now, he's having a drink, trying to forget about a woman.

“This is the best bar I've ever been to here,” he says. “I've been here mostly in the afternoon. It's a little more mellow in the afternoon, a wee bit of medicine. Now, it's more a celebration. And the food's pretty fucking good, it's pretty trustworthy, better than going to some Mexican place with a C rating. This place loosens all the cables in the brain. Doesn't matter what's on the jukebox, who's pouring drinks, it's everybody taking care of each other, in the heart of L.A. People are dancing who'd be scared to dance, laughing where they'd be scared to laugh, bartenders taking care of everyone. You're not going to run into King Eddy's, you have to find the place. It's a cushion of happiness, it's always soft.”

Liz and Winter come in. Liz has just finished a Mud Vayne video shoot, where she spent 20 hours sitting on the singer's chest, paint-animating his face. When she says she feels like she's getting the flu, Winter digs into her purse and pulls out a bottle of Herbal Care Immune System Activator. She sprinkles it on everyone's arms.

“Rub it in,” she says. It smells like herbs.

Bill watches, beaming like a proud papa. “How do you like my new generation?” he asks. “I love it.”

“Everybody comes here to not be judged,” Jeremy says. “You hang up your coat, you hang up your judgment. You're here to indulge in life. This place, it's all about forgiving and forgiving and getting back to the real world.”

Without anyone noticing, Little Honeybun has crossed to the other side of the bar, and is dancing fluidly to the Crusaders' “Street Life.” She looks like a fading though still-radiant movie star. The old men next to her scoot their stools back slightly, giving her room to glide.

“The stadiums are made by the Danbury Mint,” Joe says. “Which is like the bastard Franklin Mint.”

I'm dead.