Dispatch from Ukraine: The Road to Lviv

Good morning from a very lovely house outside of Lviv, Ukraine. I cannot say it was very easy getting here. Yesterday morning, I was eating breakfast in a hotel in Warsaw watching plans fall apart, the train ticket I had to Lviv turning out, first, to be a bus ticket, and second, there were neither any buses nor trains going from Poland to Ukraine. But I could get close to the border, to Przemysl, changing trains in Krakow. It's been a while since I have traveled by train in Europe and here's a recalled pro-tip: do not rely on the track number you have been told, and get a feel for how the air is shimmying and go with it. Wrote my first "Dispatch from Ukraine: "Let's Go. Let's Not Go," for Reason, on train from Warsaw to Krakow; that's linked below. Disembarked in Krakow, repeated read-the-air move and, because I find the town name "Przemysl" rather difficult to pronounce (it's "Sheh-muh-shl"), asked the man in the row ahead of me if Przemysl was the next stop. I think one more, he said, and that he was getting off there, too. I told him, maybe we walk together.

Vitaly lives in Rotterdam, works on offshore oil rigs and other heavy equipment jobs. He is from Odessa and was, he would tell me in not-bad English, heading home to his house outside of Odessa -- where three families were living since the start of the war - to take care of or at least check in with the women and children there; all the men had gone to fight. We walked together from the train. It was already night now, and the station in Przemysl was absolutely packed, with people trying to get further inland to Poland, with refugee organizations feeding people, just a mad crush of people. Contrary to what I had been told in Poland, there was, Vitaly found out, a train going to Lviv. We headed toward it.

It was extremely unclear, certainly to me but also somewhat to Vitaly, what was going on outside of the building from which people were being let out rather slowly. It turned out this was the disembarking station for people coming from Ukraine, women and children, a few old men and several large ungainly boys, this last a curiosity until I realized they could not fight, all men in Ukraine ages 18 to 60 are required to stay in-country to fight if necessary. Vitaly was certainly going to, he told me; that, likely, he would become part of a locally-organized division protecting his city, rather than going, for instance, to Kyiv. On the line with us were many Ukrainian men heading home - from Spain, from Poland - doing the same. Also on the line, and showing you -- or maybe more specifically showing me -- another breed that a war environment attracts was a large man telling the crowd, in a Slavic accent, "I am an international human rights attorney, can I talk to you?" Saying "no" to him were three men in paramilitary black who said they'd come from Washington State, one assumes to get into the action, through the official line was, "I've always wanted to see Kiev."

Vitaly and I and about 100 others stood in the cold for about two hours watching people disembark. I should add that this entire time I was not actually sure the train would be going to Lviv - my destination. We were finally let through, our passports stamped, and led to a train that I will describe as transport, maybe twenty cars long, old and wide, blue-and-white, the cars the refugees had just ridden from Ukraine on.

"Maybe we go in here," Vitaly said, as there was no indication of where we should go; we also, I might mention, had no tickets. We climbed aboard. The train had trash and other items on the floor and smelled a bit like a stable, which makes sense as there were no bathrooms (that I saw).

It turned out the train was going to Lviv, if very slowly until we got just across the border, when three men with semi-automatic rifles checked our passports and ID. They seemed particularly interested in my credentials, such as they are, but, no problem.

Vitaly and I talked with each other and with our neighbors, three women. One lived in Holland and grows tulips but, per Ukrainian law, can only stay out of the country three months at a time before coming home again. I am not sure it is the case - she spoke no English - but Vitaly said she might have come back to Ukraine, gathered her child, brought him or her to safety in Poland, and was now crossing back. Vitaly - who'd already told me he could not stay out of Ukraine, not while the war was going on, that he wanted and needed to come home - was now crossing back and maybe for good, he had a girlfriend here, owned a house, maybe it was time, after two decades working in Holland and Portugal and Spain, to come home.

"You want?" the tulip-woman asked, in Ukrainian, holding out a sandwich to me, one she'd packed for her child but which had gone uneaten. I really did, I was so hungry, but said, no, it's okay. Well, forget that: both she and Vitaly were on me: Eat eat eat!

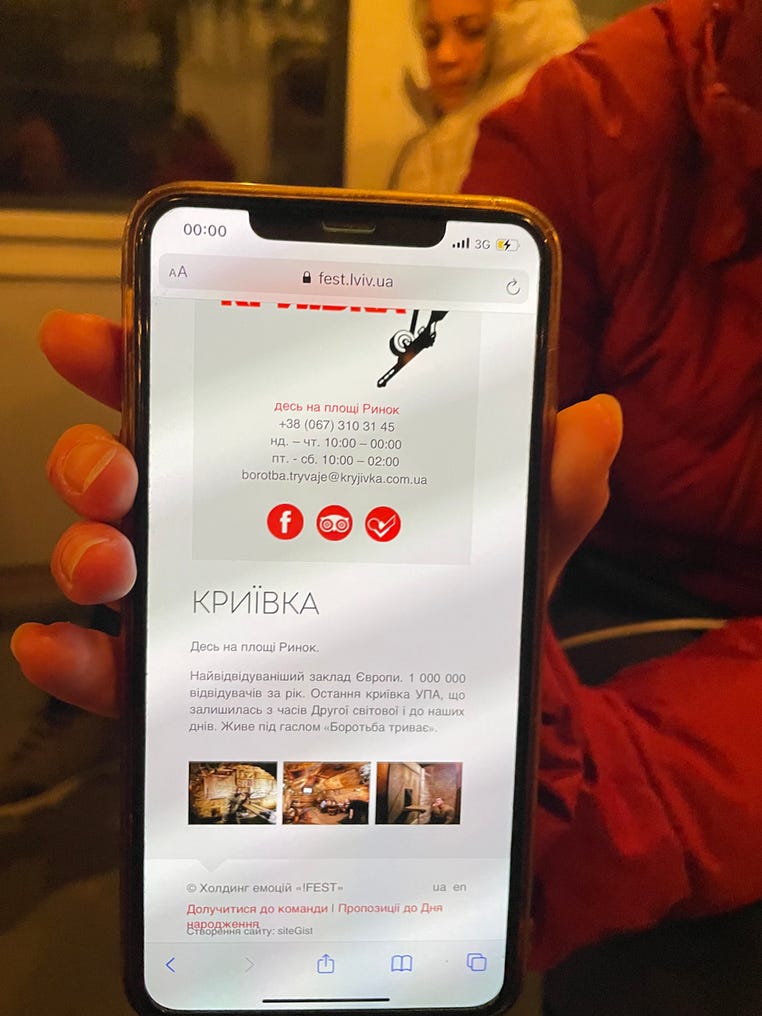

Look, it's going to sound maybe trite or sentimental, but Jesus the people I have met in Poland, in Ukraine, are just unbelievably friendly and direct, ridiculously right there. I of course took the sandwich, and within a few minutes, was able to offer her a charge for her phone. Then, the conversation turned to the universal language of food, Vitaly and the woman telling me where I should eat.

"And 'cherry drunk'," said Vitaly, indicating some drink, which made the woman laugh and laugh: She comes here to write about war, she said, and we are telling her, "cherry drunk!"

And while we were at this, go to this place, she said.

There was such crazy beautiful ease in the way she and Vitaly were talking and laughing, very much like siblings, just so easy as we hurtled through the night.

By 1am Lviv time, we'd reached the station - no one ever asked for a ticket - and got down from the train on metal steps that were maybe four inches wide with a rather big hop down. Vitaly helped a few women off, then we walked toward the main station, where the person I was to meet - the husband of someone I have never met, but whom was contacted by someone else I have never met who lives in Portland and had read my writing from there.

"Maybe it's nothing, maybe they have all already left," said Vitaly, as we headed for the station, seeing nothing of the refugees we have heard so much about... until we make one more turn, and get closer to the station, and see the dozens of portable toilets and tents set up, and what are maybe 2,000 people milling and waiting in lines, being fed by volunteers at 1am on a Monday morning.

And I am to meet someone I have never met. I know only that he is wearing a blue jacket...

"Maybe over here," says Vitaly, as we head up the big steps to the station, where he will try to get a train this night to Odessa. "Maybe that is him."

And he walks to a man who is looking at us, looking at my picture on his phone. I say yes, it is me. The man and Vitaly then hold out their hands, they take each other by the wrist, saying something that I am sure does not translate in words to this but which means, "I have gotten her this far, you will take her now, yes?" "Yes, yes." I hug Vitaly so hard and wish him safety, then get in R's nice warm station wagon and momentarily fail at not crying, from gratitude.

I will continue this story. For now, please head over to Reason and read "Dispatch from Ukraine: Let's Go. Let's Not Go." The lead is below, and if you enjoy these dispatches, please subscribe/become a Patreon member of Paloma Media, there are tabs on the upper right on the homepage xx

***

Nikolaus Sires lives in Dnipro, Ukraine. Originally from New Orleans, he bought an apartment in Dnipro, where he lives with his Ukrainian fiancée, four months ago, because he found the people nice and the area peaceful. Then, in the middle of the night on March 3, he woke to news that the nuclear power plant in Zaporizhzhia was under attack.

"The Russian troops apparently just started shelling and mortaring a nuclear power plant, basically. Shooting at it; there's video," he said. "We thought the nuclear power plant might be blown up that night."

Sires spoke to Reason's Nancy Rommelmann by phone while she was on the ground in Warsaw, Poland, on March 5. She is on her way to Lviv by train to Przemysl at the time of publication. Sires talked about being in Ukraine at the start of the war and what it's like to wonder if a nuclear power plant within an hour's drive might be melting down...

Thank you Nancy for going where the stories are. Take good care.