Dispatch from Portland 2023: Coffee With A Cop

The Portland police union president on what it's been like to police the city since 2020. "All of a sudden your name is mud and you're being questioned about everything. That was wildly destructive."

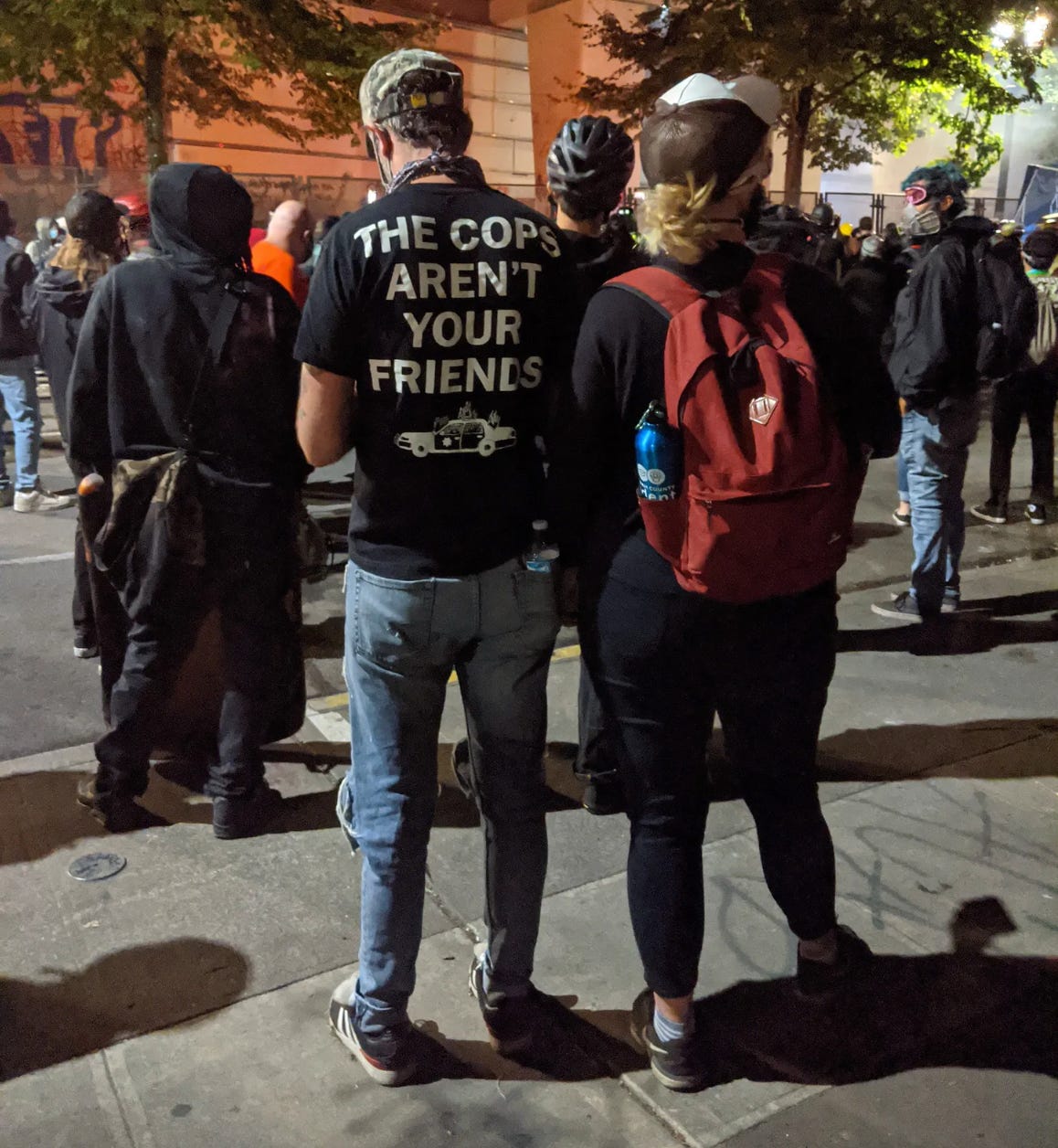

Two days after George Floyd was killed, the peaceful protests in Portland, Oregon turned violent. First target: Justice Center, the police station and holding facility downtown. Several hundred demonstrators broke in, trashed the place, set a fire. I wrote about a police employee trapped in the basement while checking in prisoners, and later asked a young couple dressed in black bloc whether they thought imperiling people in a burning building was the right thing to do.

"Do you believe that property is worth more than human lives?" asked the boy.

"Do you believe the police should be allowed to murder people?" asked the girl. "The entire police force is built on systemic racism. On keeping black people down."

Okay, I told them, but many people inside the building were black...

"We've tried for 20 years to do it another way," said the boy, who was maybe 22. "Nothing changes except with violence."

After the federal forces that Trump sent to the city on July 4, 2020 vamoosed, the police reassumed the status of public enemy #1. "All Cops Are Bastards!" was chanted an uncountable number of times. The city's bridges were tagged with SHOOT 'EM LIKE PIGS, FRY 'EM LIKE BACON. I filmed protesters squeezing little rubber pigs in cops' faces while shouting, "Quit your job!" and "Kill yourself!"

I watched, too, as lines of officers mowed through black bloc shield lines, and jumped out of the way as streams of cop cars gave chase to the hundreds of activists who swarmed the streets after dark.

It was a chaotic and electric time, one that offered identity to those engaged in the fight, a fight that came to be identified with the city itself, and not without cause. Mayor Ted Wheeler had instructed police not to arrest people in the act of protesting. Newly elected DA Mike Schmidt declined to prosecute 92% of those who were arrested. The Gun Reduction Task Force was disbanded, amid claims it targeted communities of color. And activists demanded the police be defunded by $50 million, nearly a quarter of the annual budget. (The city council responded by cutting $15 million.)

If you'd worked in Portland at that time as, say, a baker, you might have said, fuck this noise; people can find another bakery. But there's only one police force, and while some officers did quit or take early retirement, most stuck it out. Crime takes no holidays, and as the nightly protests ebbed, violent crime started to rise. The homicide rate in 2021 was the highest ever in Portland, a record beat in 2022. More than 12,000 cars were reported stolen last year. And it is no exaggeration to say downtown Portland is in something of a free fall. Foot traffic is down 40% from pre-pandemic levels, and more than a quarter of retail and office spaces are empty. Vagrancy and drug activity fill the void. Walk the area and you see people splayed out, smoking and injecting drugs, in various states of misery and madness.

The erosion of basic safety is making people insecure. Multnomah County experienced more population loss last year - over 10,000 people, for the second year in a row - than any county of comparable size in the country. And of those I interviewed this week, only one unequivocally said he and his family will stay. Others are eyeing the exits, not seeing a quick recovery, or a recovery at all.

"For five years now, I've been like, 'We've hit rock bottom; it's going to come back,'" an attorney told me. "And then we go lower, and lower, to depths I didn't ever predict."

And yet I think it is predictable. Portlanders allowed for a certain amount of lawlessness. That they did not specifically approve of this lawlessness, though sometimes they did, made it no less corrosive. People can choose to develop selective amnesia, or like a 22-year-old who doesn't have the courage to show his face, pretend that violence leads to utopia, when what it leads to is more violence, violence the city has been forced to absorb, the city takes the hit, and when rifts open, what pours out is not good.

"During that time there was almost this societal acquiescence that this violence is okay. It just was so strange," said Aaron Schmautz, an 18-year veteran of the Portland police force. Appointed president of the police union last November - his predecessor, Brian Hunzeker, got in some trouble, then got it some more - Schmautz experienced what it was like to overnight be expected to protect citizens, to fighting them.

Over coffee and pie, Schmautz offered his opinions about what it was like to work during the protests, how and if the city can build trust, and why Portland will never be the same.

His comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Nancy Rommelmann: Your union hall, the Portland Police Association in North Portland, was set on fire multiple times in late summer 2020.

Aaron Schmautz: I was in the building one of the nights. It's a small building and all the windows were boarded up. You're literally locked in and hearing fires start and trying to figure out how we're going to get out. The real issue with that particular building being a focal point was, it was adjacent to a home in a neighborhood. There was a viral video of a homeowner next door trying to put the fire out with a hose. And there's a gas meter over there, so if you burn through that, you're talking about an explosive natural gas issue. It was one of those things where there this cognitive dissonance around violence.

But the real challenge for me was at Central Precinct [in downtown Portland], when we put the chain link fences around the precinct.

NR: This was May 29, 2020, when protesters set Justice Center on fire.

AS: Yes. You had an incursion into an occupied jail and some fires lit. You cordon off a part of downtown. In the forty years I've been in Portland, I'd never seen that happen. I've been involved with crowd control in Portland, different May Day events, during Occupy [Wall Street] and after Ferguson. These were some pretty big visceral protests. Because of the video of George Floyd being murdered, and obviously that was pretty awful, it was very evident that we were going to be a part of something very different, just the level of violence and virulence surrounding the opinions towards law enforcement. You end up in this place when someone hates you and you don't even know them. What do you do with them? It is just incredible to see someone who to their ever-loving core is saying things like, "Kill all cops," and "I hope you die on the way home."

You're out here doing something that you view as heroic; that is your calling. You're doing what your community asked of you. People are burning buildings and destroying businesses. Portland people are going to black-owned businesses and destroying entire blocks of them. And all of a sudden all your name is mud and you're being questioned about your force and everything else. That was wildly destructive. We had police officers whose kids were getting kicked off sports teams because of their [parent's] occupation. The real, real ugly thing, a lot of our African American officers, the language and the hate that was just poured towards them by people, by some white protestors screaming racial epithets at black police officers in the name of racial reconciliation, which I just don't understand. It really was a very ugly time.

NR: How did the level of scrutiny from the media play into this?

AS: There was a lot of gaslighting going on in the media. From my perspective, the public interest was high and the level of attention to detail was low. People weren't spending a lot of time learning about what was happening. And there was a weird level of willingness to pretend that the things that were happening, were not. You also had a lot of combining of political issues. You had the issues with President Trump sending federal officials here and how that all went. The federal officials had different rules of engagement juxtaposed. Their force policy is different. I'm not criticizing the force they were using, but it does create this very strange problem where we're not even physically out there, but we're being criticized for the things happening.

One thing about Portland at that time: every single day, there was a very large and fairly honest and beautiful free speech event. And you'd have a lot of coverage of it. We had Damian Lillard, who was probably the most famous person in the city, do a march across the Burnside Bridge. And then night would come and something very different would happen. You would have a line of people standing there and chanting, but behind them, there would be a phalanx of very violent people. People would be bringing in weapons, throwing rocks and bottles, using slingshots to shoot metal balls, bricks, and eventually Molotov cocktails and explosives. Officers were working 30, 40 days in a row, 14-hour days, never seeing their family, exhausted, but then every day you go out and you're just being screamed at, cops were being followed home, being threatened.

NR: I watched activists take photos of police officers' license plates as they went into the garage at Justice Center. One later told me they did this so they could find and post people's home addresses.

AS: I was doxed in 2010 after an Occupy protest. In the twenty minutes it took me to get from my post on the protests line to my car, I had somewhere in the range of 100 phone calls on my personal cell phone saying, "Your wife's name is Lindsay. She teaches at this school and we're going to rape her. This is your address; these are your kids' names." I had to have a panic alarm in my house so my wife knew if someone comes, push this button. We've had officers who have had their cars damaged, brake lines cut. Our police chief had someone go all the way out to Columbia County and show up at his house.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Make More Pie to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.