David Levine, American Painter and Caricaturist

Remembering my stepdad, who died 12 years ago today

On December 28, 2009, David Levine, American caricaturist and painter, lay unconscious in NYU Langone Health in New York City. I’d flown in that day from Portland, Oregon, and went directly to the hospital. My mother, David’s wife, was there, as were my brother; Dave’s two children Matthew and Eve, and Matthew’s teenage son. I could see everyone was wiped out, having been at Dave’s bedside on and off for the past week. People needed rest but were reluctant to chance it, as it was clear Dave did not have much longer.

I on the other hand knew I was not going anywhere. I’m not sure why I was certain of this, but I was, and when it was suggested that Eve take Matthew’s son home, that my brother take my mother home, I encouraged it; it would be fine, I told them; I would stay.

I’d known Dave since I was a kid. Eve and I were in the same class at school and were casual friends. I’d been to their apartment several times, once in 1974, when we knew in advance that Paul Simon, whom David would be drawing or painting, was coming for a visit. Eve, another friend and I made absolute pests of ourselves, and while I rarely, in the 35 years I knew Dave, saw him get angry, he got testy with us that day and told us to scram.

Dave moved from his apartment into ours a year later. It was two blocks away from where he’d lived with his wife and children. Brooklyn Heights is tiny, everybody knows everybody; my mom and Dave had met and started a romance while playing mixed doubles tennis at the local club. I was too young to appreciate how wrenching this must have been for Eve’s mom, who, the year before Dave left the marriage, apparently caught on to my knowing about the affair when I saw her on the street and, instead of saying, “Hi, Mrs. Levine,” called her by her first name.

I was nobody’s idea of a good teenager, and I hesitate to think what a horror show Dave walked into that first year. But things got better, and by the time I was 15, Dave and I got on extremely well. He was unbelievably funny and fast, and I will stand by his being the best breakfast conversationalist ever; we would sit at the table every morning and mock-argue over what was in that day’s Times. I used to call him a Brooks Brothers Communist, a red diaper baby in worn Oxford cloth button-downs, shirts I often took from his closet, three of which I still have.

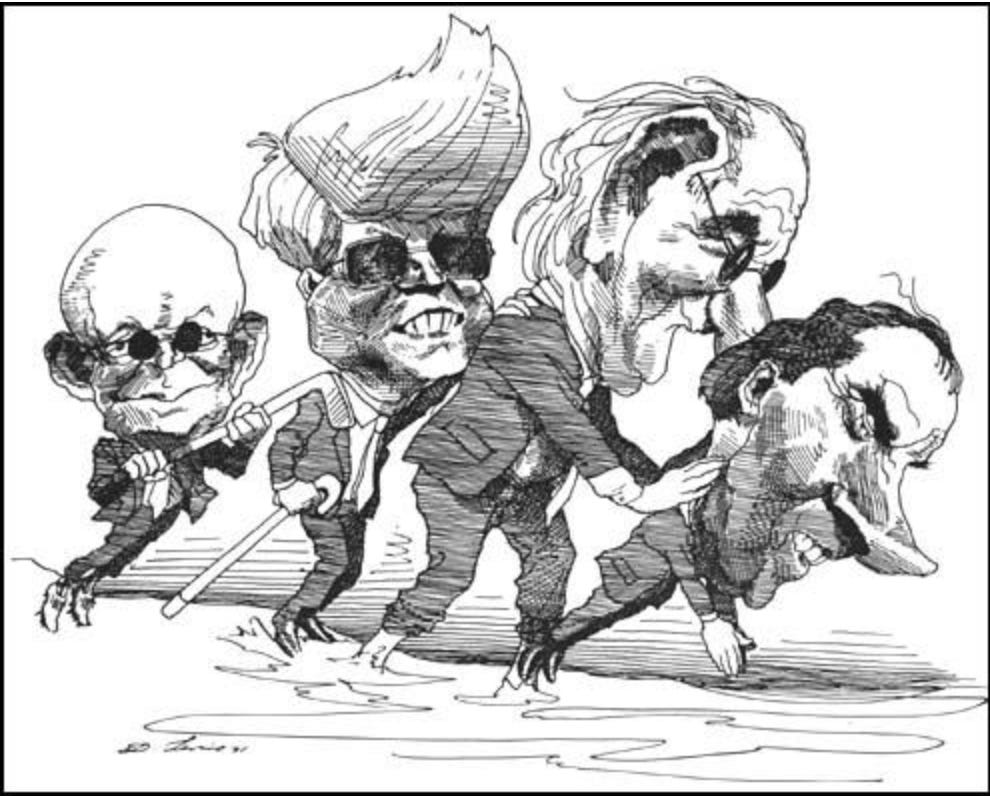

Dave was, at the time, the best-known caricaturist in the country. Magazines and newspapers obviously do not use illustration as they once did, but from the time Dave worked, the 1960s through the early 2000s, he worked constantly, for The New Yorker and The Nation and The New York Times, and, for four decades and since its inception, The New York Review of Books, where he was listed on the masthead as Staff Artist.

If Dave’s world of equally famous and hilarious artists passing in and out of our living room – I am looking at Jules Feiffer and Ed Sorel – became normal, there was also always a bit of star-stuff to it. I recall going to an opening of Dave’s paintings when I was maybe 20, at a gallery in the city, packed with people drinking wine and talking at once and wearing the sort of clothes I saw in magazines, and feeling, as Dave introduced me to the editor of New York magazine and then left me talking with him, grown-up in a way I never had. He was also a believer in people when they did not believe in themselves. About 10 years into my writing career, he told me he wanted to put me up for a Guggenheim; that he’d get Jules to write for me, too. I had told him he was crazy, to not do that; that they would never give one to me. I am incredibly moved now, remembering how much he wanted to.

Dave was a genius at what he did, of course, but it was also the regimen, of doing the work over and over and over and over. With Aaron Shikler, painter of the JFK official portrait, Dave ran an art class in the West Village every Wednesday night for 40 years. The NYRB caricatures were accomplished thus: Every Monday or Tuesday, a messenger would deliver the upcoming week’s articles, called tear-sheets, in a big yellow manila envelope. Dave would read the pieces, profiles or historical essays or book reviews or what have you. Then, he would draw, his interpretation and commentary telling you not necessarily what the stories were about, but most definitely what Dave thought about whom he was drawing!

Some people loved their caricatures, others, not so much. My mother tells a story of Philip Roth seeing David on the street in Manhattan and yelling, “David! David! Did you have to make my nose so big?” Peter Matthiessen apparently contacted Dave to ask, of a recent drawing of himself: Was it possible to add a crown of laurel leaves? (That would be no.) Margaret Thatcher, if I am recalling correctly, enjoyed hers. At various times, Dave drew caricatures of my father, my husband, my brother, my daughter, and of course my mother, for whose birthday he would draw her, in the arms of this or that inamorata, including one of her naked and being cradled in the arms of Sam Shepard. He never did draw me, but I do own several caricatures of his, including of Joan Didion, Clint Eastwood and Graham Greene.

Art was all Dave did, art and sports. He played tennis, and very well, but what he loved most was watching tennis and other sports, New York teams, mostly the Knicks but also baseball and football. He would spend hours in front of the TV, and at no time did he not also have a big art book in his lap, leafing through images by, say, Goya with McEnroe playing in the background. Dave could not cook or balance a checkbook or accomplish many other daily prosaic tasks; he regularly asked my mother when they were traveling how to turn on the hotel room shower. But art? Art he knew, knew in his skin; knew beauty. He was all about beauty.

One of my first jobs as a journalist was as a columnist for a Los Angeles magazine called Buzz. Each month, Buzz would throw a contributors’ lunch at a fancy restaurant in Beverly Hills. At one lunch, a young Russian with thick black hair and thick black glasses sat next to me. I asked him what he was doing for the magazine.

“Caric-ature,” Roman Genn said. Oh, I told him, my stepdad was David Levine, at which point – and on my daughter’s head, I do not exaggerate – Roman fell to his knees in front of me and started patting the air; no, he said, it couldn’t be, not David Levine…. I told him to get up; that I would introduce them; that they would become friends, which they did, Roman regularly calling the apartment and saying, when my mother answered, “Tell David, it’s KGB.”

It was Roman who told me, in 2003, that David could no longer draw. Dave had just done a New Yorker drawing of Obama, and it was, Roman said, too smudged.

“He can’t see,” he said, which was true. Dave had macular degeneration, and though he tried to keep drawing, and utilized various magnifiers, I think by 2007 he had stopped completely. He was also by this time dealing with prostate cancer and various heart issues. I would come home from the west coast on visits and find Dave still in front of the TV, still with the art books, unsure whether he could see either.

After everyone but Matthew left the hospital room that night, I sat by Dave. I held his hand. There was a window to Dave’s right. Midnight came and it was December 29th. Dave’s breathing slowed; a night nurse checked several times, concerned, she said, that the breaths did not pass below six per minute. Matthew and I counted breaths. It was 2 AM. A little before three, Matthew started looking for a way to charge his phone. He was behind the hospital bed, not looking at his father when I saw the skin on Dave’s face pull onto the bone and turn the color of bee’s wax; his cheekbones became very smooth and pronounced and then, there were two quick sounds, like sips through a straw, and something, a little spark, something, zipped out the window. I looked at Dave and I knew, I knew I knew I knew, he was showing me one last thing of beauty.

Gallery of David Levine caricatures at New York Review of Books

I have one of his drawings. I believe my dad, Chandler Brossard, did a story on h for LOOK, and it was in a letter he sent.