Hello from Tulsa, where I popped down after a reporting trip through Kansas, for Bari Weiss’s Common Sense - that story is here - and I don’t want to leave, the porch where I have been writing, and from I write right now, being perhaps my favorite place to have set up an office, there’s a warm wind at all times, and if I ever dip from the general population, you might do worse than to look for me here.

I have a funny thing happen (or maybe not so funny, you tell me) in that when I land someplace, especially by air, I know immediately whether it’s going to be a good writing spot. Honolulu (though I’ve yet to do any real sustained writing there); Manzanita, Oregon (where I wrote most of To the Bridge), and of course Los Angeles, maybe because I built my career there but really because it’s the place people bring their hyperbolic, desperate, beautiful dreamy-dreams, which you get to watch blossom and crash and turn into other dreams.

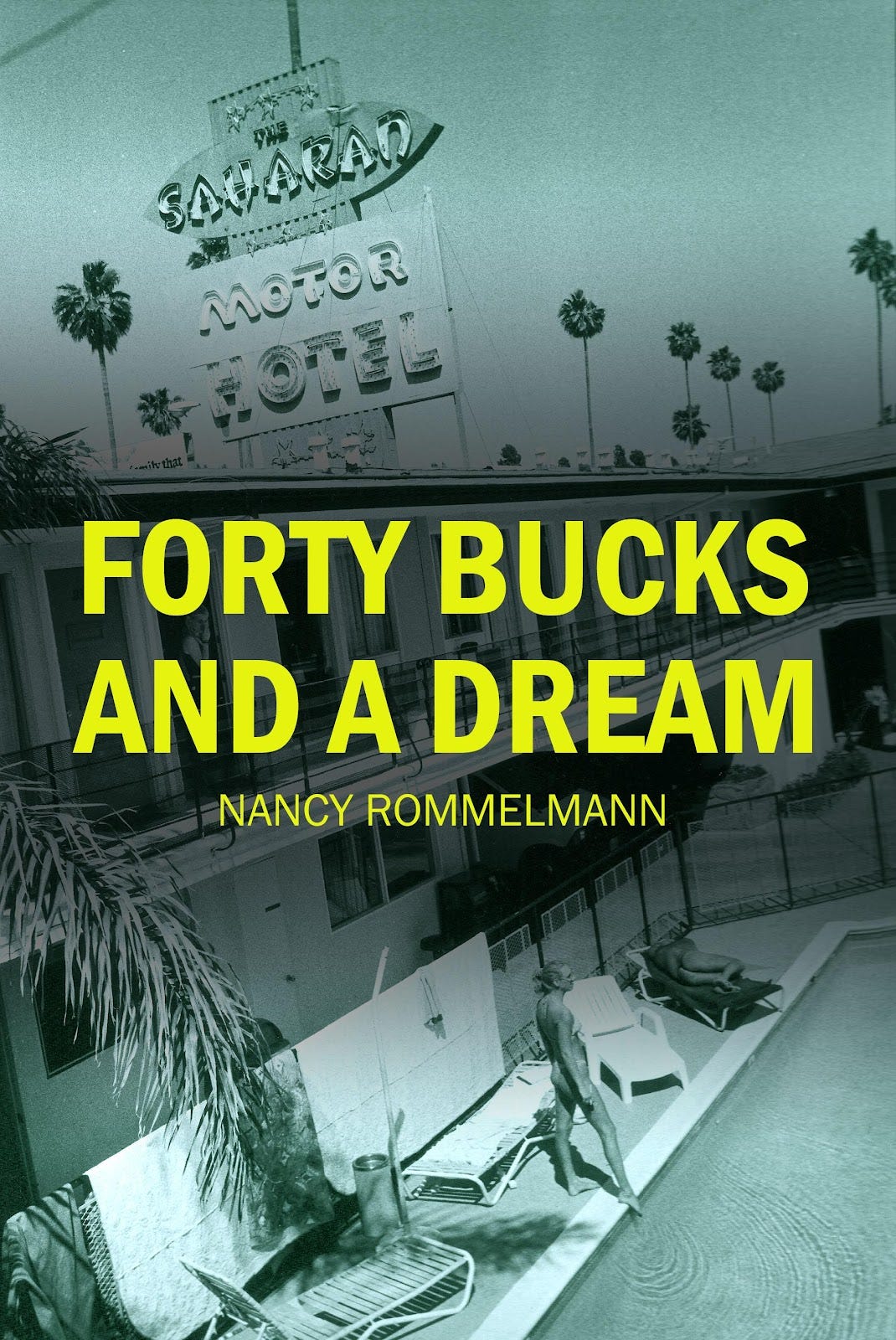

I wrote a book about these people, or maybe it’s a paean to the city; same/same. I am serializing Forty Bucks and A Dream here, and may be recording it as part of a new radio project with Paloma Media. Thank you for reading xx

Prologue

Hungry Town

On January 11, 2007 I read a New York Times obituary of a writer named Jack Winter. The article mentioned his “huge, 10-room apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side” and that he’d had a regular tennis date with former New York Knicks star Earl “the Pearl” Monroe. Winter, who a few years before his death had self-published a book called The Answer to Everything, had early success as a TV writer, for The Dick Van Dyke Show and The Monkees. But he never liked Hollywood, leaving while in his twenties, and later telling the film designer Anton Furst, “The excitement isn’t worth the uncertainty.”

I wrote down this quote for two reasons: at the time I agreed with Winter’s assessment, and because I’d received a terrible phone call on the day in 1991 that Furst jumped to his death from the roof of Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles. I’d been in Philadelphia, doing a small part in an arthouse movie I would never see, including a scene that required I walk down the street topless. In order to take this role, I had left my one-year-old daughter, who was born at Cedars-Sinai, with my mother, with instructions for her to call only in case of emergency.

The film had been a nice break from my life in LA, which at the time revolved around my not getting parts and sometimes being so broke I could afford neither toilet paper nor salt. So low was my stock of assurance that I took more pleasure than is seemly at learning that the French cinematographer, while looking at me through her lens, had said to the gaffer, “Nize teeties.”

That night in my hotel room, my phone rang. It was my mother. My knees gave out: what happened to my daughter?

“No, it’s Sarah,” she said. “She’s trying to reach you.”

I called my best friend Sarah, who was crying so hard I could barely understand her. I eventually understood that Furst, whose assistant she had been on the film Awakenings and who she did not merely admire but loved, had checked into Cedars-Sinai for exhaustion or depression and maybe substance abuse and within hours, had gone up to the roof and jumped.

I am not suggesting that Hollywood killed Furst, or that Jack Winter, who continued to write for Hollywood, including a script polish on Awakenings, was prescient for getting out young. Or maybe I am suggesting the latter. Maybe someone posthumously recalled in his obit as such a meticulous money manager he repaid with interest the investments of friends who’d backed his aborted Broadway play; maybe Winter could not stomach Hollywood’s parsimony; its ratio of consumption to return.

I’m talking about dreams here, not cash, though that, too. While it’s true every city is built on the backs of people’s dreams, LA is exceptionally resourceful in its circular logic that you will be discovered provided you believe you will be. Los Angeles will never say, hey, you’re past your freshness date; get out. Like an understanding hostess, she will make room for you in reduced circumstances; under the stairs, perhaps, but you are of course welcome to watch the paying guests, and really, she’d prefer if you did. It makes it that much more festive. Plus you are, in a sense, still part of the action.

“There’s this play in the Valley these producers really want me to do,” the actor in need of dental work tells me. He’s been told he’s just right for the role, which he’ll share with another actor, and hesitates only because it means canceling a vacation, plus there’s the $90 per performance he’ll have to pay.

For him, the excitement is worth the uncertainty.

Also, for the dry cleaner in Laurel Canyon with the twenty-year-old headshot of himself over the counter, who confides that Nic Cage just dropped off a jacket so, you never know. Also, the actress who joins the members-only Success Club, wherein she and a bunch of other people march down Wilshire Boulevard singing, “I am going to be SUCCESSFUL! I am going to land that JOB!” Also, maybe, the couple in line ahead of me at the Farmers Market, a fifty-something woman and her slightly younger male companion. She, with so much collagen in her lips she resembled Cesar Romero playing the Joker in the old Batman TV series. He, in a string tank-top that revealed a Schwarzeneggerian chest, a stunning contrast to hair fringed coquettishly above his eyes, eyes that had been surgically stretched between jubilation and terror, the same expression he might have come by naturally had he opened his apartment door at the end of the day and found sixty people yelling, “SURPRISE!” The couple might have appeared to be calmly scanning the overhead menu, but their psyches seemed trapped in some existential web, and I could not look away, despite and because doing so made my stomach hurt.

It would be easy to think, these people are nuts, or deluded, or in the throes of whatever addiction, but what proof is there that any of these are an impediment to making it in Hollywood? And if the circumstances of their dedication differed from the several hundred thousand others who make their way each year to Los Angeles, the impetus is almost always the same: they expect to find their real lives here. Like going to an ice cream store because you want ice cream, you come to LA to be the person you are meant to be, the girl on the stage, adulated, admired, loved.

It was why I came to Los Angeles, and everything I expected to happen didn’t. As an actress, I did not eat the crumbs of fame. How low did it go? The last year of my trying, I was seated next to the willowy British wife of a director in whose recent film I’d been a glorified extra. It was New Year’s Eve, and I’d blown money I did not have on an algae-green, floor-length dress, one in which I fancied, I looked like a mermaid.

“What do you do?” asked the wife, as we perched together on the edge of a divan. I told her I was an actress. She didn’t say anything as she went on looking toward the center of the room, where her husband, who would go on to make a movie about a cartoon cat, was playing the piano, until she asked, finally, “Do you get that reaction a lot?”

Ten years later, I read that the sugar solution in hummingbird feeders needs to be changed every day, lest it become impure and kill the birds it’s meant to attract. Maybe that’s why I hadn’t seen any birds at the feeder I’d hung in the window of the studio where I spent my days writing. Before I got around to cleaning it, it attracted one more bird. He looked old; his feathers were colorless and sticking up at bad angles, and I thought, I should shoo him away. But there didn’t seem any point. He was not, like the healthy vibrant hummingbirds, going to make it to the breezes coming off the coast, to sip from the trumpet vines of Pacific Palisades. I watched him teeter on the feeder as he dipped and re-dipped his needle-nose in its grimy yellow plastic flower. Maybe he thought he’d hit the mother lode; maybe he knew the dirty sugar water was going to kill him and no longer cared. I imagined him flying over my neighbor’s fence and dropping dead. I threw the feeder away.

I did not leave Los Angeles as easily.

I did not leave when the old-school screenwriter I was writing for, a man who wore pirate blouses and a captain’s cap, screamed at me at the Farmer’s Market because I misquoted the box office for Thelma & Louise.

I did not leave after a long night of partying landed me in the bedroom of a primetime TV actor whose name I could not remember but who nonetheless approached me wearing only a smile and a woman’s short black silk robe over his erection, an image so unsettling a stream of vomit shot through my nose, signal enough to get myself out of his Hollywood high-rise and walk three miles home, in the dark, without my shoes, which I could not find and which seemed prudent to leave behind.

I did not leave when the Academy Award-winning screenwriter I’d known since grade school wrapped his arms around my waist in the lobby of CAA and said, to someone, “She’s a real writer.” Which made me look toward the lobby’s soaring wall of glass with a serious desire to smash it. Instead, I went outside and stood on the corner of Beverly and Wilshire and thought, for the zillionth time, how beautiful Los Angeles is, if only at night.

I did not know I would leave until my new husband, who was not bewitched by uncertainty and had no interest in Los Angeles’s tantalizing maybes, sat me on our sofa and said, “I need to get the fuck out of here.”

The things he found intolerable – the desperation; the personal assistant who made him wait for his paycheck in the driveway of her boss’s house while she got a massage; the nose jobs and boob jobs and platypus lips and calf implants, each an attempt to make the person both better than and the same as everyone else, a zero sum game for everyone but the plastic surgeons – had over the years become what I found most tender about the city, to say nothing of my bread and butter.

When I mentioned to my neighbor, an international fashionisto who lived in a glass house across from ours, that I might leave Los Angeles, he smiled.

“Getting out,” he mused, a hairless miniature dog shivering at the hem of his caftan. “It’s everyone’s fantasy.”

Read: Chapter 1: Forty Bucks and a Dream: The Lives of a Hollywood Motel

That's quite a prologue! ... and a nice writing spot to hang out, for sure. I look forward to the chapters and, as a lover of stories told in voice I heartily endorse the idea of the radio project. Just had a thought -- perhaps you have one or two regular audio narrators, but perhaps guest narrators would be interesting as well?

When I'm new to a city I move around looking for a writing spot like a chipmunk looking for nuts. I almost always end up in the quiet corner of a public space -- where I can both have my little nest to write, and where I can be reminded that its unhealthy to be entirely in your own head and removed from the world. Which is after all what I want to write about.